Cousins by blood – enemies by inheritance

Duke Knud. A mural from Vigersted Church.

I have as long as I remember been interested in history, including the Danish

history of course.

However, it is not all the historic periods that I find equally exciting, but

the two periods that I find most interesting when it comes to Danish history are the Germanic Iron Age (about 375 to 750 AD),

not least the part called the Migration Period (which I will probably

return to in another article)

and then what is

called the High Middle Ages, from about

1000 to 1300. I even push it a bit forward to the period after the Viking Age (by

definition from the attack on Lindisfarne in 793 to Harald Hardrada's defeat

against Harold Godwinson at Stamford Bridge in 1066).

The story that is told here takes place in the beginning of the 12th

century, shortly after the Viking age was over by

definition although some Viking raids still took place but not on any larger

scale.

There were many interesting people during this period, although most of those we

know from written sources are royals, noblemen or members of the higher clergy.

The history of ordinary citizens was rarely recorded unless these ordinary people came into contact with the nobility.

That's why this article differs from most others on this page. It has been told

more than once before, and by professional historians, but I will tell the story

anyway as I find it very interesting and a good example of how family

relations didn't exactly meant that you were close in this period, actually

quite the contrary. In

Denmark we have an old saying "Frænde er frænde værst". I haven't been

able to find an English equivalent, nut "frænde" is an old Danish word for

"kinsman", and "værst" simply means "worst". So one translation could be

"Relatives are your worst enemies" or something like that. This article is a

proof of that.

The key figure in this article is one of my favorites from the middle ages, and although he never became king, he was the son of a king and became the father of a king. I'm not going into a complete biography in this article, but will concentrate on his death. I will give a brief intro though, to what happened before as it plays an important part, and also a short follow-up on what happened in Denmark after his death. In this article I use the Danish version of person's names, but I ngive the English version of same names if any, the first time I introduce a new person.

|

Mod sønden der står en

herlig mand. Knud Hertug er hans navn. Han lod sit unge liv for svig. Det voldte os så stort et savn. |

Towards the south stands a wonderful man. Duke Knud is his name. He lost his young life to deceit. It caused us such a loss. |

The text on the left is first verse of from a 1971 song by Danish band, Skousen and Ingemann, from their album "Herfra hvor vi står". The text on the right is a literal translation with no intention of bringing the mood or the rhythm of the verse. And the protagonist of this article is exacly the man who lost his life, Duke Knud, better known in Denmark as Knud Lavard (Canute Lavard in English). But let me begin with an introduction to the man.

Knud was the son of King Erik (Eric) I of Denmark, known as Erik the Good and his consort Bodil (Boedil) Thurgotsdaughter. Knud was the only legitimate son of the king, and he was destined replace Erik when he died. Knud was born in the royal hall in Roskilde in 1096. His father, Erik is known to be the only Danish king born in the small village of Slangerup on Zealand. In 1103 King Erik and Queen Bodil went on a pilgrimage to Jerusalem, but the king never reached The Holy Land as he got ill and died during a stay in Cyprus. In Gesta Danorum, Saxo Grammaticus tells about Eriks death and burial: This island had hitherto been known for the oddity that no one could be buried there, for if in daytime a body was buried in the earth, it was immediately thrown back out in the night. Here the king was attacked by fever, and when he felt that his last hour was near, he asked that his body be grounded near the capital on the island; though the Earth used to throw out others, he said, his body would be allowed to rest there in peace. He was then buried as he wanted, and his body caused the earth to abandon its old grudge and that, while it would not previously allow any human body to rest there it accepted not just him, but also others were allowed to lay there in peace. I wonder what they did with the dead bodies of that island until 1103? With this statement Saxo is probably preparing the earth for later claims that Erik's descendants were blessed by God.

Queen Bodil managed to get to Jerusalem but died there, according to legend while she was visiting the Mount of Olives. Not until almost two years later their deaths were confirmed in Demark. At that time the throne was not hereditary, but the kings were elected by the "Thing", an assembly made up of the nobility and the free people of the community. As Knud was only 7 years old at that time, Erik's brother Niels was elected king. Niels would later be known as Niels the Old as he lived to be almost 70, a high age at that time. Knud was put into the care of a very wealthy nobleman from Zealand, Ebbe Skjalm Hvide, the head of the very powerful Hvide clan. Knud grew up with Skjalm Hvide's sons, and especially befriended Asser Rig who considered him a brother. As a young man Knud joined the forces of Lothar (Lothair), Duke of Saxony. In 1125 Lothar became king of Germany and 1133 he became Holy Roman Emperor.

After helping King Niels in battle against the king's newphew (son of the king's sister), Prince Henrik (Henry) of the Wend tribe, the Obotrites, in 1115 Kong Niels appointed him "Jarl (earl) af Sønderjylland" with the task to protect the Danish borderlands from Wend attacks. Knud carried out this job successfully, and finally made peace with Henrik, on behalf of King Niels. When the peace agreement was settled, Knud helped Henrik acquire his mothers inheritance, which was the original cause of the controversy between Niels and Henrik. After that Henrik and Knud became close friends. Knud also ridded the area of some Danish nobles and wealthy farmers who had taken advantage of the unrest to rob the poor people. "He spread the enemies, killed the robbers and hung the thieves, in short, he freed his country of birth for all oppression", as one source put it. One story tells that "a nobleman abused his power to maltreat the poor and oppress his neighbors. Knud heard about this while he was in Skåne (Scania - in present day southern Sweden,) and immediately he returned to Sønderjylland, arrested the man, accused him, interrogated him, convicted him and sentenced him to be hanged. The accused did not deny his guilt but thought he should be free because he was related to Knud Lavard: "I am closely related to your family, do not hurt your own family"! Knud's answer was that because the man was a member of his family, he would also have to get a special treatment when it came to his punishment, and the more he was above others in his relationships, the more he should also be above in his punishment. Knud then raised a ships mast on the gallows hill, and hanged his relative from it." At the same time he was very generous to not least his own "hird" (his housecarls), but also to the poor people living on his lands. The "hird" gave him the nickname he later went by, "Lavard", which actually means "bread giver", corresponding to the English title "Lord", which has the same meaning. In 1116 Knud married Princess Ingeborg of Novogrod and they had three daughters, Christine (or Kirsten), Margrethe and Katrine. In 1127, after the death of Prince Henrik, Knud Lavard bought the office as Prince of the Obotrite's ("Knjaz" in Wend) from King Lothar, and he was given the title "Duke", a title he also transferred to his Danish possessions. This was the first time the titel Duke was used in Denmark, and as the Duchy of Schleswig didn't yet exist, the relevance of the title is questionable. Formally, the duchy was first established when the later King Valdemar the Victorious, became Duke of Southern Jutland, and the Duchy of Schleswig wasn't established until 1375, when Duke of Schleswig be became the official title.

The remains of Knud Lavard's Chapel outside Haraldsted on Zealand.

I'm not going to bother you here with the political power game between Knud, on one hand vassal of King Niels Vase and on the other vassal of King Lothar, but it made the potential heirs to Niels' throne fear (and probably rightly so) that Knud would want to be elected King of Denmark when Niels died. Niels had only one son, Magnus, but there were several others who would like to be king, not least descendants of Niels' brothers, Harald III Hen, Knud (Canute) IV The Holy and Oluf I Hunger, who had all been kings before Niels, and also Svend, called "Throne Claimer" who died just before he could be made king at the thing in Viborg. Among these children only a few were legitimate, while the rest were sons of the kings with various mistresses, but them being illegitimate meant nothing at the timne, since having illegitimate children was normal to royalty and as they all were in any case children of the king, at lleast the sons were possible heirs to the throne. In fact, all four mentioned kings and including Knud's father, Erik I The Good, were illegitimate sons of Svend (Sweyn) II Estridsen, who had at least 20 children out of wedlock each with a different mistress. Of these children 13 were sons whos descendants would all like to lay claim to the Danish throne. Closest to the throne though was Magnus, who was the legitimate son of the ruling King Niels.

And now we are almost where we want to be. Magnus considered Knud to be the most serious competitor to the royal power in Denmark. Magnus, called "The Young" or "The Strong," and in the Roskilde Chronicles referred to as "Denmark's Flower", was 12 years younger than Knud, and he feared that Knud would be the favorite to be elected king. First, he was older and more experienced in both war and government, and second, he was quite popular, especially in Southern Jutland and in Zealand, where he had support not only from the mighty Hvide clan, but also from other nobilities and even ordinary citizens. Magnus tried to become King of Sweden in 1125 when his cousin, King Inge the Younger died, but although he was elected by the people of Western Götaland, he was rejected by the people of Svealand who had the exclusive right to elect the kings of Sweden, and later Magnus had to leave Sweden when elected Swedish king, Sverker Karlsson the Elder, conquered Western Götaland, and Magnus had to return to Denmark.

I have mentioned a couple of times that it was true correct what Magnus (and others) feared, that Knud would try to win the throne when Niels died. However, he was accused of wanting the royal power, even while Niels was still alive, which he most likely didn't. At a meeting in Ribe King Niels himself blamed Knud for his ambitions, and accused him of calling himself "king" without being one. In his reply, Knud rejected these accusations and explained that his Wend title was not "King", but "Knjaz" or "Knees", which meant "Prince" not "King" and that his nickname given to him by his hird, "Lavard", just meant Lord, not king either. Neither the hird nor any other of people recognized him as a king. Knud's rejection of the accusations was so convincing that it was impossible for his opponents to attack him again in public, although not least the nobleman Henrik Skadelaar (Henrik had been hurt in his leg during a battle, and walked with a limb, hence the nickname - Skadelaar translates to "Hurt Thigh) continued to slander him to the king. Henrik Skadelaar was the son of King Niels' brother, Svend Throne Claimer, who had hoped to become king after Erik the Good, but died before he could make it, after which the throne went to Niels. Henrik was thus a cousin of both Knud and Magnus, and himself also in play for the throne when Niels died, which never became relevant though as Henrik died in 1134, three weeks before Niels. Henrik and Magnus had to conceal their efforts to get rid of Knud but they collaborated with several of Knud's relatives to get him killed. In the beginning, Knud's brother-in-law, Hakon Jyde, married to Knud's half-sister, Ragnhild, also joined the conspiracy without knowing what the plot was all about, but when he found out that it was about murdering his wife's brother, he withdrew from the plot. However, he had sworn not to tell of the conspiracy to anyone, and that oath he promised to keep, so he could not warn Knud. After the murder, he joined the group of noblemen who tried to get Magnus made responsible and punished. Among the others who participated in the conspiracy was Ingrid Nielsdatter's husband, Ubbe Jarl. Ingrid was the illegitimate daughter of King Niels and hence Knud's cousin. Also Ingrid and Ubbe's son Hakon Skåning was part of the conspiracy. Another was a German singer who was present at court, and whom Knud already knew from the court of Lothar. There is no doubt, at least not to me, that King Niels knew what was going on and accepted it as he wanted his own son on the throne, but if he was actually active in the plot, is more doubtful. "Then Magnus eventually got the permission from his father, as it was said, to take care of his welfare and to get his competitor out of the way," Saxo Grammaticus wrote about the matter in his Gesta Danorum.

In December 1130, Knud travelled from his home in Schleswig to Roskilde by invitation from Magnus, to celebrate Christmas with his uncle Niels and his family. Magnus had expressed a wish that Knud should take care of Magnus' wife, Rikissa of Poland and their little son, Knud, while Magnus himself went on a pilgrimage, and he would like to discuss the details. Knud's wife, Ingeborg, who was pregnant and close to giving birth, was suspicious of Magnus and warned Knud not to leave, but he refused to stay, perhaps because he still trusted Magnus. Ingeborg herself had to stay in Schleswig because of the coming birth. According to Saxo Grammaticus, Knud knew what he was doing and he went to Roskilde for a reason. If he stayed away, "he would make shame of mutual trust, blood relations and the family connection "According to Saxo, he did not attend the party because he was unaware of the risk, but because of the things he valued like confidence, community and family made him feel that he had to take the risk. Henrik Skadelaar and Magnus had planned for Magnus to kill Knud during the party which lasted for several days, and Magnus did make several attempts, but all unsuccessful. Maybe the spirit of his mother, Margrethe Fredskulla, who had managed to "pour oil on the waters" between the two cousins, and managed to make Magnus refrain from attacking Knud, was still exercising influence on his decision, even though she had died earlier that year of edema (also known as dropsy). According to Saxo Margrethe Fredskulla was very fond of Knud, and on her death bed she had asked him to "bear with Magnus and treat him good even when he acted bad" This report however, is contradicted by Helmold's Chronica Slavorum (Chronicle of the Slavs), which states: "For Niels' son Magnus, who was also present at this event (a meeting in Schleswig between Knud and Niels), was indescribably incited when his mother said to him, "Do not you notice that your cousin has all seized the spire and is already a king?" These words incited him, as mentioned and he started hatching plots to get Knud killed". Probably Saxo is the more correct here, as Margrthe elsewhere is described as wise and peaceful queen. Knud's wife, Ingeborg, got news of the plot (maybe from Hakon Jyde) and sent a messenger to once again warn Knud, but still he didn't take the warning seriously.

Knud Lavard's tomb in Sct. Bends Church in Ringsted on Zealand.

Towards the end of the Christmas celebration (on January 6th 1131), Knud and his party left for nearby Haraldsted where Knud's cousin Cæcilie (Cecilia) and her husband Erik Jarl of Falster lived. Cæcilie was the daughter of Knud's uncle, Knud IV the Holy, who had died several years before Knud Lavard was born. When he was murdered, Cæcilie and her twin sister, Ingegerd was put in care of Knud's father, Erik Evergood, where they grew up. She was about 10 years old when Knud was born, and the two them had a very close relationship, and she most likely considered herself to be Knud's older sister. Early in the morning of January 7th 1131, a messenger from Magnus, arrived in Haraldsted Gård, the home of Cæcila and Erik. The messenger was the German singer, whom Knud already knew and whom he trusted, and it was therefore easy for him to invite Knud to a friendly meeting with Magnus in the woods outside Haraldsted, not far from Cæcilie and Eriks home, Magnus had already asked Knud if he would meet and talk about the forthcoming pilgrimage, which Magnus claimed to be leaving for as they had not managed to do so during the Christmas party. Magnus' men had hidden themselves in the woods already the day before the meeting. Cæcilia, who herself had lost her father to murderers, suspected that Magnus would try to kill Knud, and warned him not to go, but again he discarded the warning, as he still refused to believe that Magnus would do him any harm. He therefore brought with him only two squires and two servants, and he had to be persuaded to bring his own sword at all. When he reached the place of the meeting, he made his men wait at a distance outside the woods, while he went alone to the meeting. According to the accounts of the murder, Magnus was waiting for him, sitting on a fallen log, but got up, spoke briefly with Knud and embraced him. When he was embraced Knud noticed that Magnus was wearing a chainmail, underneath his clothes, and when he began to ask Magnus, what that was about, Magnus' men broke out from the woods screaming and yelling and before Knud got hold of his sword, Magnus had pulled his and

|

Og kløvede hans skal

ned til det højre øre. Sådan slog han Knud. |

And chopped his skull down to the right

ear. That's how he slew Knud. |

as mentioned in the Skousen and Ingeman song.

After the killing, first Henrik Skadelaar and then the other conspirators pierced the body with their spears before they disappeared. The men that Knud had brought had no time to react before it was too late, but they brought the body back to Haralsted Gård. Magnus, on the other hand, was happy. Saxo has this description: "Magnus went to Roskilde, satisfied and with joy that the wicked Murder had now been accomplished, and after he had gotten rid of his competitor, he was sure he would ne elected for the throne, he even showed his triumph over the wrongdoing that he should rather have been ashamed of, and he felt pleasure from it and he mocked and scorned Knud's holy wounds, which he rather full of remorse should have cried over." After the murder, the sons of the Hvide clan asked the King to let them bury Knud in Roskilde Cathedral, the traditional burial place of the royal family, but this request was denied by King Niels, who feared that this would possibly make the Roskilde citizens raise against Magnus. Knuds body was instead taken to Ringsted and buried in the abbey church there. Very soon after the burial miracles started to happen at the grave. Later his remains were transferred to the new church called Sct. Bendts Church, named for Benedict of Nursia, founder of The Order of Sanct Benedict, which Knud's son King Valdemar I the Great built in Ringste. You can still visit Knud's grave in the church, where also his son, Valdemar I and his grandsons, Knud VI and Valdemar II and several other members of the royal family are buried. At the spot in the woods where he had been murdered, a spring emerged and the water here was also miraculous, A chapel was erected nearby. His half brother Erik II Emune (The Memorable) and later his son Valdemar the Great argued that Knud should be canonized as a saint, and he was actually canonized by Pope Alexander III in 1169. On June 25, 1170 his Reliquary, with his bones were placed in a shrine in Sct. Bendts Church in Ringsted. On the same day Valdemar I's son, 7-year old Knud (VI) was elected as his father's co-regent.

Through the Middle Ages the chapel and the spring was visited by pilgrims, but after the Reformation, the chapel as well as the spring was forgotten and went into oblivion. In 1883 the chapel was rediscovered and excavated, and the ruin can be visited today at Knud Lavardsvej just outside Haraldsted. No trace of the spring has ever been found. A visit to the site shows that the woods must have retracted since 1131, as the chapel is actually 200 meters (600 feet) from the current forest edge. 7 or 8 days after Knud's death, Ingeborg gave birth to his son Valdemar, or as Saxo writes: "But to ensure that he who had been so deserving both for an earthly ending and an eternal purpose, should not be without offspring, the divine God blessed him after he died, for the eighth day after, Ingeborg gave him a son named Valdemar after his great grandfather on his mother's side." Valdemar's great grandfather was Vladimir II Monomakh of Kiev, and Valdemar is simply the Danish version of russian Vladimir. As Valdemar was fatherless, he was placed in care of Asser Rig Hvide, a son of Knud's own foster father, Skjalm Hvide and like a brother to Knud. Here Valdemar was raised together with Asser Rig's own two sons, Esbern Snare and Absalon (later to become Archbishop of Lund).

Unfortunately, Knud's assassination did not mean peace and calm, neither for Magnus and his co-conspirators nor for Denmark. Knud's younger half-brother, Erik, who wanted revenge, received support from the Zealand nobility, not least members of the Hvide clan, raised an army and started a war against Niels and Magnus.

The traitor, Ubbe Jarl was caught in his castle and hanged there, but the war went back and forth, mostly back in Erik's opinion, as he suffered defeat after defeat, especially in the Battle of Værebro on Zealand. After this defeat, Erik had to flee to Skåne with his army, which made his opponents give him the nickname Erik Harefod (Harefoot), but only for a short while. Niels came to Skåne with his fleet. Here they landed, but were overwhelmed by by Erik's army, reinforced by German horsemen, sent by Lothar, who had now become the Holy Roman Emperor, and who also wanted revenge for the murder of his protégé, Knud. Niels tried to retreat, but before the army reached the ships, the battle began. This became what we know today as the Battle of Fodevig, a mere 10 miles south of present day Swedish city, Malmö. In this battle Erik for once won and won a decisive victory. Niels managed to escape, but Magnus and Henrik Skadelaar and five bishops who was on the king's side were all killed. Niels fled to Jutland, and at one point he went to Schleswig. One might wonder why and many historians have already, why Niels went there, as Schleswig was Knud's most important stronghold where he had his strongest support, and where the citizens and nobility there had loved Knud very much. It has been suggested that Niels believed that he could persuade the citizens and nobility to support him against Erik, but that proved to be an impossible task, and the visit ended when citizens forced their way into the house where the king was lodging and killed him there. The year was 1134 and after that Erik Emune became king. However, only after a conflict with his and Knud's half-brother, Harald Kesja. Harald proclaimed himself king and tried to be elected at Urnehoved Thing in Southern Jylland. Harald, however, was not popular and was never accepted by anyone but the ones who had elected him, and already the following year he was killed by Erik, who also killed most of Harald's sons. Erik's own reign was also short. He was a harsh and unpopular ruler and he was assassinated by the a nobleman named Sorte Plov (Black Plow) at Urnehoved Thing already in 1137. According to historian Arild Huitfeldt, writing in the late 16th and early 17th century, in his large work Chronicle of the Kingdom of Denmark from around 1600, King Erik's nephew Erik Håkonssøn stepped forward with sword in hand, but the nobleman told him to calm down, seeing as how he – Erik – was next in line for the throne, being the only adult male in the royal family: "Put away thine mace, young Erik. A juicy piece of meat hath fallen in thine bowl!" According to legend, Sorte Plov escaped with his life and Erik Emune was followed by his nephew, Erik III Lam (Lamb, probably a name alluding to the term "God's Lamb" for Jesus in the New Testament, a nickname given for Erik's piety), who was the son of Ragnhild Eriksdatter and Haakon Jyde, who was originally a part of the plot against Knud Lavard. Erik Lam was probably only elected king as all the other obvious candidates for the throne were minors. Erik abdicated voluntarily, as the only Danish regent ever, in 1146 due to a severe febrile disease, and died in Sct. Knuds Abbey in Odense later that year. And then it was once again time for civil war. This time between Magnus The Strongs' son, Knud, later Knud V, Erik Emune's son, Svend, later Svend III, also known as Svend Grathe, and Knud Lavard's son Valdemar, later Valdemar I or Valdemar the Great. This civil war deserves an independent article, and it may very well get it one day. It was this war that included the so-called Bloodfeast of Roskilde and ended with the Battle of Grathe Heath, after which Valdemar in 1157 became the sole king of Denmark.

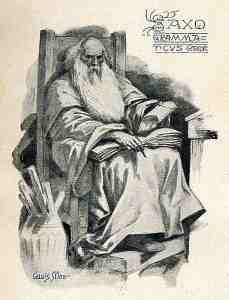

Saxo Grammaticus,

drawing by Louis Moe for the 1898 edition of Gesta Danorum. A fine illustration

of a man, that for all we know didn't get much older than fifty.

Saxo Grammaticus,

drawing by Louis Moe for the 1898 edition of Gesta Danorum. A fine illustration

of a man, that for all we know didn't get much older than fifty.

One of the most detailed sources of the assassination of Knud Lavard and the events that preceded and followed the murder, is Gesta Danorum (Deeds of the Danes) by Saxo Grammaticus. Here Saxo spends a whole book of the 16 books the works consist of, Book 13, on King Niels and the events surrounding him. This particular book was probably written as the second or third book around 1186 (historians suggest that book 14 was written first).

According to Saxo, there is no doubt that the main antagonist in the plot against Knud Lavard was Henrik Skadelaar, who (still according to Saxo) hated Knud Lavard of all his heart. Henrik managed to persuade both King Niels and Magnus several times, in addition to other noblemen, to go against Knud.

Saxo didn't like Magnus either because of the evil deed he did and because he committed th crime on a holyday (Epiphany). He also describes the other conspirators in very negative terms, as they were not only committing an evil murder, but also acted blasphemous. Niels is described as a relatively weak king, which he probably was, who was wise enough to let his skilled and clever wife decide, what he probably did, but this was certainly not what Saxo expected from a king (or any man at that). To Saxo, a man should be strong and decisive and the women stay in the background and not get involved in any decision-making. Knud, on the other hand, is described almost as the saint he had already been canonized as before Saxo wrote his history. Here it is important to remember that Saxo was a monk or priest, and therefore he was opposed to anyone wo went against God's will and especially people like the conspirators that in his opinion committed blasphemy by swearing falsely or in this case, cheating, so they could actually swear the truth but still lie. If what Saxo tells is true, the conspirators had been lying down, when they were plotting the murder, because then if they were ever questioned, they could swear that it was the truth that they had not plotted against Knud, neither standing nor sitting as it was custom when you took oath in trials at that time. This was to Saxo maybe even worse that the murder itself, as they tried to cheat God himself.

It is also important to remember that Saxo was very biased. He wrote for Absalon, Valdemar I's foster brother, he had known Valdemar personally and had most of his knowledge from Absalon and other members of the Hvide clan. During the at least 25 years it took him to complete his History, the ruling kings were Knud VI and Valdemar the Victorious, both sons of Valdemar I, and Saxo did not want to displease neither his employer, Archbishop Absalon, nor the kings. Saxo mentions that his own father and grandfather had served as soldiers in Valdemar's army, so he had a great respect for the king, who was dead though when Saxo began his history.

Saxo has some interesting stories along the way For example, he explains the hostility between Knud Lavard and Henrik Skadelaar that that the latter believed that Knud had prompted Henrik's wife to leave him for a lover. His wife dressed as a man and sneaked out of the castle with her lover and both escaped. Henrik pursued the couple to Aalborg and brought his wife back while the lover got away. Henrik was convinced that Knud was behind both the wife taking a lover and the leaving, even if Knud had absolutely nothing to do with matter. Neither did Henrik like the way Knud "dressed as a German noble" not as a Dane. And he accused Knud of dressing in purple colors because he already considered himself a king. Saxo believes that Knud responded very politely, but in reality he made a serious insult to Henrik: "Knud replied that they (his clothes) protected as well as a lambskin peasant's coat (that Henrik was wearing), because he thought it more polite to this way relate to Henrik his boorish ways in a kind manner than by making threats and harsh words, so he was therefore pleased to shame him with his homemade clothes when he himself was insulted for his foreign and magnificent clothing".

Saxo didn't care much for Knud's half-brother, Harald Kesja either. He is described as being an evil and cruel tyrant when he served as a regent for his father during his pilgrimage. Therefore, says Saxo, he was not elected king when his father was reported dead. Later, he tried several times to gain the royal power, and he began raiding as a Viking, not abroad but mostly plundering around Roskilde, where the royal castle was.

And finally to end the article with an unhappy love story! If you know Vestervig Kirke in Thy (in northern Jutland) you probably also know the story of Liden Kirsten and Prince Buris, who according to the legend are buried in the cemetery. If you haven't seen the place, and ever come to Denmark, it's worth a visit. The church is the largest villagf churrch in Denmark. I mention Vestervig and the legend in my video: My Country 2: Northern Jylland that can be found on my Daddy Sage YouTube channel. The legend goes like this:

Liden Kirsten and Prince Buris were in love, but the king, Valdemar I The (in the case not so) Great, would not accept the relationship. He killed Liden Kirsten by making her dance herself to death. She was taken to Vestervig and buried there. The king then had Prince Buris blinded and gilded, then taken to Verstervig as well. Here he was chained to the church wall. The chain was so short that he could just reach Liden Kirsten's grave. When he finally died he was buried, not next to the woman he loved, but they were buried foot to foot so to speak.

This sound evil, and is if it were true. It is not though. The story doesn't match the historical facts. The historical Prince Buris was a supporter of King Valdemar for some years but turned against him and was taken prisoner and incarcerated in the dungeon beneath Søborg Castle in northen Zealand in 1167 where he died later the same year. Liden Kirsten is last mentioned in any historical source in 1141 and a DNA examination of the remains in the two graves shows that it is a brother/sister couple in their fifties. Unfortunately the inscription on the stone has been unreadable for hundreds of years, so nobody knows who the couple was, or why they were buried like that. But if the legend had been true, the king's actions might be understandable. Little Kirsten was his older sister, also a daughter of Knud Lavard, and Prince Buris was the son of Henrik Skadelaar, his father's murderer. And such a relationship might very have brought the king's mind to a boiling point.

Unfortunately apparently only the first 9 books of Gesta Danorum is translated to English, so I have had to try to translate the quotes from them myself. As I'm not too acquainted with Medieval English the translation is rather poor. I have used the Danish text of Saxo's Latin, translated by Frederik Winkel Horn in 1898. This translation can be found on the Norwegian page Heimskringla Wiki at http://heimskringla.no/wiki/Danmarks_krønike. An excellent page with many good source texts, in Danish and other Scandinavian Languages.