|

| |

Was Jesus married - and to whom

This will most likely be a rather long article,

much longer that the previous ones, and most likely longer than any that I willl

publish about this subject in the future, but who knows? In this

article I try to join two of the articles from my Danish pages, "Was Jesus

Married?" and "Who were the many Marias".

Was Jesus married?

The question in the headline for this section

has occupied many people for quite some time, but not least after Dan Brown

published his novel, "The Da Vinci Code" in 2003, the interest in Jesus' marital status flourished. A simple Google search for the question in the headline,

yields more than 32.000 hits from the search term "Was Jesus married?"

When I originally became interested in Jesus as a historical figure in the early

1980s, there were a few books, among those that I read, that discussed this

subject. One was the 1982 book "The Holy Blood and The Holy Grail", written by

Michael Baigent, Henry Lincoln, and Richard Leigh. Although not least the second

part of the book, concerning the Priory of Sion was based on a hoax, that the

authors actually believed in at that time, the remaining parts, especially the

part that concerns Jesus' possible lineage, was based on the authors research

in biblical and nonbiblical sources. The other book I read was a 1970 book by

William Phipps, "Was Jesus Married - the Distortion of Sexuality in the

Christian Tradition." Both books arrived at the same conclusion, namely that

Jesus was actually married. Since then many other researchers have reached the

same conclusion, and probably even more have reached the exact opposite.

The four canonical gospels do not mention with a single word that Jesus was married,

and neither do any of the apocryphal texts. At least not directly. Both sides of

the discussion use this as an argument for their own point of view. Those who

claim that Jesus was not married argue that if he were, then surely it would

have been mentioned in the gospels. Those, who believe he was married use the

argument that if he weren't married, it would have been so extraordinary for the

Jews of that time that it would have been noticed if he wasn't married. So the

absence of information can be used as an argument both for and against a

marriage.

The canonical gospels

Let me take a look at what the sources are

actually saying about the issue. As mentioned above, the four canonical gospels do not mention

anything about Jesus being married. In Matthew 19:18, Jesus tells a young man to

keep the commandments. When the man asks what commandments, Jesus mentions these,

including "you shall not commit adultery". Earlier in the same chapter, Jesus is

quoted for answering some Pharisees who ask him about divorce: "“Haven’t you

read,” he replied, “that at the beginning the Creator ‘made them male and female,’

and said, ‘For this reason a man will leave his father and mother and be united

to his wife, and the two will become one flesh’? So they are no longer two, but

one flesh. Therefore what God has joined together, let no one separate." (Matt.

19: 4-6) And a few verses later, in a conversation with the disicples: "Jesus replied, “Moses permitted you to divorce your wives because your hearts were

hard. But it was not this way from the beginning. I tell you that anyone who

divorces his wife, except for sexual immorality, and marries another woman

commits adultery.” The disciples said to him, “If this is the situation between

a husband and wife, it is better not to marry.” Jesus replied, “Not everyone can

accept this word, but only those to whom it has been given. For there are

eunuchs who were born that way, and there are eunuchs who have been made eunuchs

by others — and there are those who choose to live like eunuchs for the sake of

the kingdom of heaven. The one who can accept this should accept it.” (Matt.

19.8-12).

The last quote is interpreted differently by different scholars. Some interpret

it as if Jesus says that he himself has chosen to live like a eunuch and that it

is a good thing, but not everyone can live up to it. Others believe that Jesus

is trying to say that those who live like eunuchs for the sake of the "kingdom of

heaven" have misunderstood what it takes to enter the kingdom. They thus

interpret this sentence as meaning that those who were eunuchs from birth or

have been made eunuchs by others may enter the kingdom, while those who make

themselves eunuchs will not.

The apocryphal writings

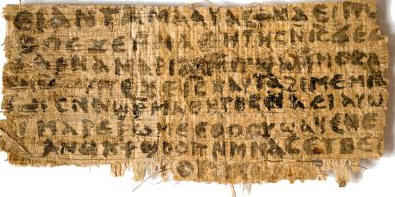

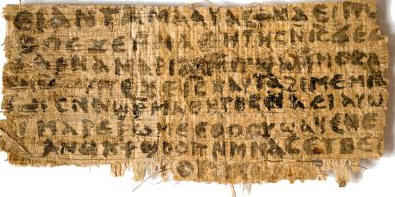

Papyrus fragment containing the

so-called "Gospel of Jesus' Wife", that are most likely a late forgery. The

papyrus cabon date back to medieval times. The fragment contains the line: "...Jesus

said to them, 'My wife...she is able to be my disciple'".

Dan Brown suggests in

his novel that if you look at the apocryphal writings, these contains several

elements that suggest that Jesus was married. And not only was he married, but

was married to Mary Magdalene. However, it is not that easy. In fact, none of

the apocryphal writings (gospels and other) mention anything about Jesus'

marital status.

The Gospel of Thomas, which is believed

to be one of the earliest apocryphal writings,* contains primarily some

statements from Jesus, but no action and therefore no context. A Mary is mentioned two places in the

gospel, first time in verse 21 (the gospel has no chapters). In this case she

asks Jesus "Whom are your disciples like?" (another translation has "What

are your disciples like?") and Jesus replies with a longer explanation that

the disciples are like servants living in a field that they do not own ... "

(and in another translation the word "servants" is translated to "children").

Like most statements in Thomas the reply is very esoteric and many of the

question/answer dialogues seem a bit what we in Denmark would call a "Goddag

mand, økseskaft" (English "Hello man, ax handle!" - click

to get an explanation of the expression) type of answers. But the answers

would probably have made sense to a Gnostic audience in the second century. An

example: The disciples have asked Jesus if they should enter the Kingdom of

Heaven as babies. To this Jesus answers: "Jesus said to them, "When you make

the two into one, and when you make the inner like the outer and the outer like

the inner, and the upper like the lower, and when you make male and female into

a single one, so that the male will not be male nor the female be female, when

you make eyes in place of an eye, a hand in place of a hand, a foot in place of

a foot, an image in place of an image, then you will enter the kingdom."

(Thomas, 22). This statement is often taken as proof that Jesus is arguing for

marriage ("make male and female into a single one"). The second time Mary is

mentioned is in the last "verse", which is possibly a later addition. Here Simon

Peter says to them (the disciples): "Make Mary leave us for females don't

deserve life!" Jesus chooses to refrain from defending women's right to life,

but instead responds, "Look, I will guide her to make her male, so that she

too may become a living spirit resembling you males. For every female who makes

herself male will enter the kingdom of Heaven." (Thomas 114). Jesus probably

don't intend to make Mary become a man physically (sex change was not on the

agenda in those days), but rather symbolically, and the passage may need to be

understood as if that Jesus will teach her to understand the Kingdom of God in

the same way a man understands it. I should probably add that neither of the two

places talk about Mary being Magdalene. It is later interpretations that it was

she who was in question.

* Some scholars date the Gospel of Thomas as

early as around year 60 AD, that is, as early as or even earlier than the

canonical gospels. Others date it as late as 140 AD. However, many scholars

agree that the oral tradition underlying the gospel goes back a long way. When

it is difficult to date, it is because it consists only of isolated statements

without context.

The Gospel of Peter only mentions Mary

in connection with the resurrection and discovery of the open tomb. In this

gospel the name Magdalene is mentioned, but she is only mentioned as a female

disciple of Jesus. (Gospel of Peter, 50). This gospel dates from the end of the

second century.

In The Gospel According to Mary or just

the Gospel of Mary, Peter says, "Peter said to Mary, Sister we know that the

Savior loved you more than the rest of woman". (Mary 5.5.) Later in the

gospel, Andrew doubts whether Jesus actually had said what Mary claims he had

said: "Say what you wish to say about what she has said. I at least do not

believe that the Savior said this. For certainly these teachings are strange

ideas" (Mary 9.2), and Peter wonders "Did He really speak privately with

a woman and not openly to us? Are we to turn about and all listen to her? Did He

prefer her to us?" (Mary, 9.4). The gospel is believed to have been written

sometime in the second century and scholars do not actually agree on which Mary

gave the name to the gospel. Most believe that it must be Mary Magdalene, while

others believe that this may not be the case, but do not name which else Mary it

may be, though the Mary mentioned may have been Jesus' own mother, whom he

probably loved more than most other women.

Other apocryphal writings that mention Mary

Magdalene include Sophia of Jesus Christ (or "The Wisdom of Jesus Christ"),

and Pistis Sophia ("The Faith of Sophia" or "The Faith of Wisdom").

Sophia is a female "deity", whom the Gnostics claimed was a female equivalent of Jesus.) In the

latter, Jesus says of Mary Magdalene that "her heart is more focused on the

Kingdom of Heaven than all her brothers (the disciples)" and later that "she

is blessed more than any other woman on earth." Mary is the Blessed, who

will inherit the whole "Kingdom of Light" Mary is also mentioned in the book "The

Dialogue of the Savior", which is a conversation between the "Savior" who is

never called neither Christ nor Jesus in this book, and his disciples, including

Mary. None of these writings mention anything about a marriage between Mary

Magdalene and Jesus.

The apocryphal writing that most people refer

to (including Dan Brown) when arguing that Jesus was married, is The Gospel

of Philip. The gospel is strongly Gnostic in its construction and is

probably fairly late, perhaps from the end of the third century or the beginning

of the fourth. The Gospel contains some references that can be interpreted as if

Jesus was married and that Mary Magdalene was his wife. Most of the gospel is

about marriage as a sacred mystery. No less than 25 times a bridal chamber is

mentioned. Two places in the Gospel mention Mary Magdalene. The first time it

says, "There were three who always walked with the Lord: Mary, his mother,

and her sister, and Magdalene, the one who was called his companion. His sister

and his mother and his companion were each a Mary." 'His' should probably be

read here as "her", meaning that it was Jesus' aunt named Mary, not his sister,

but he can also easily have had a sister with a name, as many names were

repeated within the families. Later in the Gospel it is stated: "And the

companion of the [Lord was] Mary Magdalene. [The Lord] loved her more than all the

disciples, and used to kiss her often on her mouth. The rest of the disciples [wondered

why]. They said to him "Why do you love her more than all of us?" The Savior

answered and said to them,"Why do I not love you like her? When a blind man and

one who sees are both together in darkness, they are no different from one

another. When the light comes, then he who sees will see the light, and he who

is blind will remain in darkness." The square brackets represent words that

are missing in the original manuscripts.

It is especially the word "companion" that has given rise to a presumption that

Jesus and Mary were married. Among others, Baigent et al believe that the

original Greek word, "koinonos", can only be translated as "life companion", ie wife. Others, such as Mark D. Roberts, a Texas pastor, writer, and

blogger, argue that this is wrong and that the word simply means "partner, like

in "business partner"." It is actually correct that the word can mean "partner"

(that someone has joint ownership over something), but it can also mean "one who

shares", and implies a relationship that includes "sharing something intimate".

And it could directly mean that two parties entered into an agreement to "live a

life where everything was shared for the rest of their lives" and the word was

simply used in the sense of marriage. So we do not know exactly today in what

context the word was used in the Gospel of Philip. But that may well be the

last-mentioned meaning. However, this is not the same as saying that Jesus was

married to Magdalene. In addition, the gospel is probably too distant from the

events in time to know the facts.

First Epistle to the Corinthians (1 Corinthians)

Thirteen letters in the New Testament are

attributed to Paul. Seven of these are usually considered "genuine", while the

others are considered pseudoepigraphs, that is, written by an anonymous author

but attributed to Paul. Among the letters is "Paul's First Epistle to the

Corinthians" or just "1 Corinthians". Most scholars agree that this is one of

the genuine letters that was actually written by Paul himself around 53 or 54.

The letter was written while Paul was staying in Ephesus in present-day Turkey

and addressed to the congregation he had founded in Corinth, Greece. Chapters 7

through 14 deal with questions from the Corinthian congregation that Paul

answers. Chapter 7 begins with "Now for the matters you wrote about:

It is good for a man not to have sexual relations with a woman. But since sexual

immorality is occurring, each man should have sexual relations with his own wife,

and each woman with her own husband". (1 Cor. 7.1-2).

In verse 7, Paul continues, "I wish that all of you were as I am. But each of

you has your own gift from God; one has this gift, another has that." Paul

was unmarried at this time, but it is uncertain today whether he had always been

single or whether he had become a widower at an earlier time. In any case, he is

alluding to his unmarried status. In verse 8 he continues: "Now to the

unmarried and the widows I say: It is good for them to stay unmarried, as I do.

But if they cannot control themselves, they should marry, for it is better to

marry than to burn with passion." (1 Cor. 7.7-9) In verses 10 and 11 Paul

writes about divorce: "To the married I give this command (not I, but the

Lord): A wife must not separate from her husband. But if she does, she must

remain unmarried or else be reconciled to her husband. And a husband must not

divorce his wife." (1 Corinthians 7.10-11).

In 2006 James Tabor, Head of the Department of Religious Studies at the

University of North Carolina, published in the book "The Jesus Dynasty". In the

book he concludes that Jesus' family, that is, his (half) sisters and (half)

brothers, founded a "royal dynasty", but Tabor also concluded that Jesus himself

was not married. However, he later changed his mind, and today he believes that

the 1 Corinthians supports a presumption that Jesus actually was married. As a

starting point, he primarily uses the above passages. Elsewhere in these

chapters, Paul clearly emphasizes that he has the Lord behind him in his

statements, and he takes up Jesus' authority whenever he can, but in this very

passage he refers only to his own example. Tabor is convinced that if Paul had

known that Jesus was unmarried, he would not have failed to emphasize it, so

when he does not, Tabor perceives it as an indication that Paul knew that Jesus

was in fact married. (Tabor, James: www.jesusdynasty.com/blog - The blog

is no longer online).

A further argument Tabor found in chapter 9, verse 5, where it says, "Don’t

we have the right to take a believing wife along with us, as do the other

apostles and the Lord’s brothers and Cephas" (By "sister" is meant here a

sister in the faith, not a sister by blood - Cephas is Simon Peter). So the other apostles were

apparently married, and so were Jesus' brothers, and their wives traveled with

them.

Other sources

Although itis not the official view of The

Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, there were quite a few former

Church Fathers of the Mormon Church who believed that Jesus was actually married,

and there are still some who do. The arguments are, among other things, that

even though there is mentioned nothing about Jesus' marital relationship in the

Bible, it does not matter. The Bible does not contain the whole truth, but only

the things that are necessary for people to be saved, and Jesus' possible

marriage has nothing to do with this, therefore there was no reason to mention

it. Some members of the Church also believe (as well as do most other scholars

by the way) that the Bible, as we know it today, has been subjected to numerous

edits, conscious or not conscious, in which elements have been removed and/or

added. Church-founder Joseph Smith wrote, among other things, "Ignorant

translators, careless copyists, or manipulative and corrupt priests have made

many mistakes." (Teachings of the Prophet Josph Smith, 1843). The Church's

official position is that Jesus was neither a hermit nor an ascetic, but not

that he was necessarily married. One of the church's former leaders, Orson Hyde,

President of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles of The Church of Jesus Christ of

Latter-day Saints from 1847 to 1875 and thus the church's supreme prophet next

to the church leader, believed that the wedding in Cana was Jesus' own wedding

(more on that below).

One of the early church fathers of the Christian Church was Irenaeus, who was

bishop of Lyon in Gaul (present-day France) in the late 2nd century. He had a

great influence on the shaping of the teachings of the early church, and he was

a sharp opponent of anything that was just reminiscent of heresy. His most

famous work is the book "Against Heresies", which he wrote around 180 AD. In

this book (five volumes) he speaks vehemently against not least Gnosticism,

which he perceived as the most serious heresy of all. Nevertheless, he himself

claimed that Jesus had undergone every critical stage of human existence, thus

sanctifying these. This included birth and death, but also marriage and

parenthood. Irenaeus thus, saw no heresy in the fact that Jesus would have been

married and fathered children. He actually had to have done that, in order to

sanctify marriage.

Arguments for and against Jesus being married

One argument is often put forward by

representatives of both sides of the debate, namely the absence of information

about Jesus' possible marriage in the contemporary sources. Those who claim that

Jesus was not married argue that if he had been, it would naturally be

highlighted in the Gospels. Conversely, proponents of the idea that Jesus was

married use the absence of information to say that at that time it would have

been so unlikely that a man was not married that it would have been highlighted

if that had been the case.

Let me take a closer look at the arguments. Proponents of the "marriage theory"

stress that at that time Jewish men were usually married. On top of that, they

usually got married relatively early. Marcello Craveri, an Italian Bible scholar,

wrote in his 1966 book "The Life of Jesus" that in Judaism, marriage was a

sacred duty. In the Old Testament, those who did not marry and produce children

were from time to time compared to murderers. John Spong, a now retired

episcopal bishop and still active author from Newark, New Jersey, wrote in 1992:

"Of course, these data are not sufficient for a final conclusion, but

together they constitute an argument suggesting that Jesus may have been married.

and that Mary Magdalene ... was his wife. These data were suppressed but not

wiped out by the Christian church even before the Gospels were written down."

(Born of a Woman: A Bishop Rethinks the Birth of Jesus). So these are modern

scholars who argue that Jesus must have been married.

Others

argue against this, including Mark D. Roberts, whom I mentioned above. He and

several others cite some sources from the time around Jesus' active period or

shortly after. One of the three most frequently cited sources is Philo of

Alexandria, a Jewish philosopher who lived between 10 BCE and 40 AD. He tried to

reconcile Greek and Jewish philosophy, but despite the fact that Philo lived at

the same time as Jesus and was interested in Jewish sects, he does not mention

Jesus and his movement with a single word (I have an explanation for this, which

will appear in a later article). It is also in this context that Philo is used

by these opponents of the marriage theory, precisely because of his interest in

Jewish sects. He wrote extensively about, among others, the Essenes. Philo wrote

of this sect, "...they repudiate marriage; and at the same time they practise

continence in an eminent degree; for no one of the Essenes ever marries a wife,

because woman is a selfish creature and one addicted to jealousy in an

immoderate degree, and terribly calculated to agitate and overturn the natural

inclinations of a man, and to mislead him by her continual tricks." (Hypothetica:

Apology for the Jews).

The other two sources are both by the same author, Josephus or Flavius Josephus.

He was a Jewish/Roman historian who participated in the First Jewish–Roman War

(66-73), in which he served as military commander of the Jewish troops in

Galilee. After being captured by Vespasian's troops in 67, he switched sides and

became part of the court surrounding the Roman emperor. Two of his books, "The

Jewish War" and "Jewish Antiquities" were written during this period, and the

Essenes are also mentioned in these writings. In "The Jewish War" he writes,

among other things: "They neglect wedlock, but choose out other persons

children, while they are pliable, and fit for learning, and esteem them to be of

their kindred, and form them according to their own manners. They do not

absolutely deny the fitness of marriage, and the succession of mankind thereby

continued; but they guard against the lascivious behavior of women, and are

persuaded that none of them preserve their fidelity to one man" (Wars, Book

II, Chapter 8). In "Jewish Antiquities" one can read: "There are about four

thousand men that live in this way, and neither marry wives, nor are desirous to

keep servants; as thinking the latter tempts men to be unjust, and the former

gives the handle to domestic quarrels..." (Antiquities, Book XVIII, Chapter

1).

It is therefore

a fact that there were people in Palestine who did not marry. However, not all

Essenes practiced abstinence and avoided marriage. It depends on where in

Josephus' works you read. In fact, there is some indication that the sect was

divided into two factions. One lived in secluded enclaves, often in desert areas.

In these groups they practiced the said abstinence from marriage and sexual

intercourse, and spent much of the time on religious studies and debates. The

other faction lived in the cities, where group members often acted as healers.

This faction practiced marriage, and, like other Jews at the time, had plenty of

children. Thus, it is certainly possible that Jesus may have practiced

abstinence as some Essenes, who certainly inspired him in other areas (e.g.,

healing), but most likely he was not a member of any of these groups.

Mark D. Roberts

wrote on his blog: "Unlike other Jewish teachers of that time, Jesus had

close relationships with women, many of whom were his followers, and who learned

from him," and Roberts continues, "But nothing in The New Testament

suggests that Jesus was ever married to any of these women or to any other woman

for that matter. " (Mark D. Roberts at Beliefnet:

http://blog.beliefnet.com/markdroberts/ - blog is no longer online). I quote the

Gospel of Luke who mentions the women travelling with Jesus: "After this,

Jesus traveled about from one town and village to another, proclaiming the good

news of the kingdom of God. The Twelve were with him, and also some women who

had been cured of evil spirits and diseases: Mary (called Magdalene) from whom

seven demons had come out; Joanna the wife of Chuza, the manager of Herod’s

household; Susanna; and many others. These women were helping to support them

out of their own means." (Luke 8.1-3).

Contrary to

Roberts, exactly the fact that Jesus had women in his company is considered by

others to be proof that both they and he were married. Thus, among others,

Andrew Norman Wilson, an English writer and journalist who was originally a

declared atheist (which he claimed in 1980), but who later found the faith (claimed

in 2009), wrote in 1985: "In Jesus' day almost every interaction with a woman

outside the immediate family would have led to frowns in the outside world"

(How can we Know, 1985). So it would simply not have been possible for an

unmarried woman to travel around the countryside with Jesus.

Another

argument against Jesus being married is that his wife is not mentioned in

connection with the crucifixion. As Jesus hanged on the cross, he decided that "The

Disciple whom he loved" the (also called The Beloved Disciple) should take care

of his mother when he himself was gone, but he doesn't mention anything about

what will happen to his wife. For those who believe that "The Beloved Disciple"

was Mary Magdalene, this does not pose a problem (I have already mentioned the issue

of The Beloved Disciple in a

previous article). For those who believe that the

beloved disciple was someone else, it need not be a problem either. When Jesus

does not deal with his wife's future, it may simply be because it has already

been agreed on before he was arrested. Another possibility is that Jesus' wife

was not present at the crucifixion, in which case she was not Mary Magdalene, as

many suppose - I will get back to this below. Jesus may also have become a

widower before the crucifixion, but neither are there any indications of this in

the sources.

One other argument that have been used in favor of Jesus' marriage has been that

it was not possible for him to be a teacher if he was not married. According to

the Gospels, both the disciples and others repeatedly call Jesus "rabbi",

meaning exactly "teacher". Some quote the Talmud: "An unmarried man can't be

a teacher". So if Jesus was a teacher (rabbi), he must have been married. On

the other hand, it is argued that Jesus was not a rabbi in the true sense of the

word, but was just called "rabbi" by the evangelists. But if the Talmudic

quotatiuon had been cited correctly it could be turned down more: "A man who

is unmarried should not teach children, because of the mothers who visit the

children. No woman should teach children, because of the fathers who visit the

children. The reason is that he may be tempted by the mothers who visit their

sons." (Mishneh Torah, Chapter 2, Halakha (Law) IV cf. Judaism in Practice,

Lawrence Fine). Notice that the verse does not mentions any marital status for

female teachers as they should not teach children at all. Also notice that

Talmud only applies the rule to the teaching of children, not teaching of

adults.

One last

argument in favor of Jesus being married, which I actually think is better, is

that the Pharisees and "the teachers of the law" constantly attack Jesus for "being

and behaving different". He must defend one action and another, but the

Pharisees, who certainly did not practice celibacy, never ask Jesus to explain

why he is unmarried or why he has no children. Such a blatant breach of the

Jewish custom and religious obligation of the day would - whether Jesus were

Essene - have been used against him. Bruce R. McConkie, another member of the

Quorum of the Twelve Apostles of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints

from 1972 to 1985, wrote in his book "The Mortal Messiah," published between

1979 and 1981: "Men Married when they were about sixteen or seventeen years

old and almost never later than when they were twenty; and women married

somewhat earlier, often when they were fourteen or younger. " (The Mortal

Messiah, Volume 1). Sidney B. Sperry could add "It is well known that the

Jews regarded marriage as a religious duty." (Sidney B. Sperry, The Letters

of Paul). This duty dates back to Genesis: "As for you, be fruitful and

increase in number; multiply on the earth and increase upon it." (Genesis

9.7). If Jesus was not married and had children, there was every reason for his

opponents to attack him for this very thing, but they did not!

My personal position is that the arguments for Jesus being married are stronger

than the arguments that he was not. Not least because I am of the belief that

the historical Jesus was a fairly ordinary Jew who agreed to abide by the law

and follow Jewish custom. "Do not think that I have come to abolish the Law

or the Prophets; I have not come to abolish them but to fulfill them. For truly

I tell you, until heaven and earth disappear, not the smallest letter, not the

least stroke of a pen, will by any means disappear from the Law until everything

is accomplished. Therefore anyone who sets aside one of the least of these

commands and teaches others accordingly will be called least in the kingdom of

heaven, but whoever practices and teaches these commands will be called great in

the kingdom of heaven." (Matt. 5.17-19).

The wedding in Cana

The

wedding at Cana, Paolo Veronese, 1562-1563, Musée du Louvre. Paris:

Was this Jesus' own wedding and if so, to whom? The

wedding at Cana, Paolo Veronese, 1562-1563, Musée du Louvre. Paris:

Was this Jesus' own wedding and if so, to whom?

If Jesus was

married, is there any mention of such a marriage in the New Testament? There is

actually a mention of a wedding, namely the wedding in Cana, which is known only

from John. (John 2.1-12). In this story Jesus and his disciples are attending a

wedding. (It should be noted that a wedding party at the time could last up to

14 days, so it is not just a short stay in Cana on that occasion). Jesus' mother

was present as well, and she behaved as if she were the host: "When the wine was

gone, Jesus’ mother said to him, “They have no more wine.” Here she implies that

Jesus, should get some more wine. Jesus is a little stubborn, but his mother

trumps him and tells the servants to do what Jesus says.

If Maria was not in charge of the party, there was no reason for her to be

responsible for procuring more wine, and if she did not have influence, there

was no reason for the servants to obey her. Then Jesus performs his first

miracle (in this gospel) and transforms water into wine. This miracle is so far

from those he later performs, and is to his own advantage what none of his other

miracles are, so I wonder if he has not procured the wine in some other way?

Later it is said: "They did so, and the master of the banquet tasted the

water that had been turned into wine. He did not realize where it had come from,

though the servants who had drawn the water knew. Then he called the bridegroom

aside and said, “Everyone brings out the choice wine first and then the cheaper

wine after the guests have had too much to drink; but you have saved the best

till now.” The master of the banquet has thus just been told by the servants

that Jesus has turned water into wine (or at least provided the wine) and yet he

addresses the bridegroom. It seems strange if the groom was not the one who had

provided the wine, ie Jesus himself. It is of course possible that the wedding

feast is celebrated for one of Jesus' brothers, but many agree that it sounds as

if it is Jesus' own wedding that is described here. But if Jesus was married,

then who was his bride? Most agrees thar the name of his wife was "Mary", but as

there a plenty of Marys in the gospels, I will take a look at those before I try

to answer this question- and I will get back to Cana in a future article about

Jesus' miracles in which I will try to come up with a scientific (or at least

rational) explanation for this and other miracles in the gospels.

Mary, Mary, Mary and ...

The name Mary is not mentioned at all in the Old Testament, but in turn several

times in the New Testament. Thus the Gospel of Matthew has seven references to

persons with the name; Mark has four; Luke has 15 and John also 15. In addition,

the name is mentioned once in the Acts of the Apostles and once in Paul's

Epistle to the Romans (normally just known as Romans). An article I read

recently tried to explain the many Marys that lived in the first century, by

claiming that women had

no significance, and therefore no effort was made to come up with different names for them,

which is why 70% of all Jewish women were named Mary - or rather Miriam, which

is the Hebrew form of the name (Maryam in Aramaic), while Mary is the English version of the Greek Maria.

I have not been

able to confirm that there were actually that many Marys in the Jewish areas at

that time from other sources, and I actually doubt it, but the name has certainly

been popular at least in some circles. No one knows exactly where the name comes

from and hence not even what it means, making it even harder to explain why it

suddenly became so popular. Some scholars believe that it may come from an

Egyptian word, 'mr' meaning "love", but it might also be linked to the Hebrew words, 'mr'

("bitter") or 'mry' ("rebellious"). If it is true that the name began its

popularity in the first century BC and the first century AD, this does not sound

unlikely. The whole area was buzzing with rebellious thoughts in the centuries

before and after the alledged time of the birth of Christ; first against the Syrians and

later against the Romans. Along the way, there were factions that rebelled

against the Maccabee rulers, against the Herodian rulers etc. In such a period

of rebellious mood, someone might have felt inspired when naming their daughters

and sons. The growing use of the name in the following centuries, on the other

hand, is of course due to the spreading of Christianity. The name and its

derived forms, eg Marie and Maria are considered to be the most common girls

name in today's western world.

But back to the

biblical Marys. At this time, surnames were not used, so you had to resort to

nicknames to distinguish people with the same name from each other. Thus also in

the New Testament. An example of another way of distinguishing occurs in John

14:22: "Then Judas (not Judas Iscariot) said...". Here Judas is

identified as who he is not, but that is not the ordinary way. Typically,

nicknames are used that either tell where the person originates from, who they

are related to (mother of, daughter of and so on) or a trait of those in

question, eg James the Less. Unfortunately, we do not know today whether the

different sources have used different nicknames about the same Mary, or whether

all the Marys who appear under different nicknames are actually different people.

That's what I'll look at in more detail below.

In the New

Testament, six or seven people are called Mary. When the number is uncertain, it

is especially due to one of the passages, where it is difficult to determine

whether one or two people are being referred to. More on that below. The six Marys are: Mary, mother of Jesus; Mary Magdalene; Mary of Bethany; Mary,

mother of James and Joses; Mary, mother of John Mark and Mary, wife of Clopas.

Number seven is a Mary, who is mentioned in Romans, and she is not further

identified. Some sources even have eight Marys, but I will get back to that

later. Let me take a closer look at the seven.

Mary, mother of Jesus

Here there is no doubt about the identification. Mary is referred to as "the

mother of Jesus" in most places where she is referred to. On the other hand, the

Gospels do not tell much about her. However, Matthew and Luke agree that she was

engaged to a man named Joseph (more in the article

Jesus' Parents - was Jesus a

poor carpenter). An engagement (or betrothal) had the same status as a marriage,

but the two betrothed did not live together, but stayed with their respective

parents. The engagement period was usually about a year and then the fiancés got

married and moved in together. Girls typically became engaged when they were 12

or 13 years old, while boys were usually bnetween 17 and 19 years old. Mary was presumably a completely normal Jewish girl, and thus was at most 13 when she became

engaged to Joseph. No one knows today who Maria's parents were. A tradition from

the 2nd century, mentioned in the apocryphal Gospel of James, tells that her

parents were Anna and Joachim. During Catholicism, Saint Anna was celebrated in

Denmark as one of the most important saints. In the Catholic Church, she is

referred to as the "Holy Mother of God's Most Holy Mother". The Gospel of James

tells us that Anna and Joachim were rich and pious, and that they often gave to

the poor. This is contrary to what several biblical traditionalists believe when

they claim that Mary was the daughter of poor parents from Nazareth.

Since very early times, there have been some who believe that the genealogy

mentioned in Luke (Luke 3: 23-38) is in fact not the family of Joseph, but Mary.

The one mentioned in Matthew (Matt. 1.1-17) This, of course, explains why the

two genealogies are different, but not why Joseph appears on both of them -

and not Mary.

According to Matthew, Joseph's closest ancestors were James or Jacob (his

father), Mattan (his grandfather) and Eleazar (his great-grandfather). In Luke

Joseph's father was Eli, his grandfather Mattat and his great-grandfather Levi. Mattat and Mattan are close

but probably not the same person. Interestingly, Jesus is mentioned in the Gospels as

a descendant of David - despite the fact that Joseph was not his physical father.

It is therefore strange that it is Joseph's genealogy that is interesting, not

Mary's, not least because kinship among the Jews during this period was

inherited through the mother, not the father. Two Mormon scholars, Blair van

Dyke and Ray Huntingdon, both from Brigham Young University in Provo, Utah, agrees that the genealogy of Luke represents Mary, but goes a step further and

equates Mattan with Mattat (even though their ancestors are not the same). In

this way they come to the conclusion that Eli and Jacob in the two genealogies

were brothers and that Joseph and Mary therefore cousins! (from "Sorting

Out the Seven Marys in the New Testament"). Other scholars also claim

that Eli/James and Joachim were cousins, so Mary was Joseph's second cousin,

but there is no proof of that from any contemporary or later sources.

Author Robert Graves believed (and used in his novel King Jesus from 1946) that Mary was a princess of Michael's lineage (a royal lineage that

goes even further back in Jewish history than the lineage of David) and that she

married Antipater, son of Herod the Great and that Antipater was the father of

Jesus. After Antipater's death, she married Joseph and Jesus grew up as his son.

Joseph Raymond ("Herodian Messiah", 2010) believes that Mary was the daughter of

Antigonus II Mattahias, the last ruler of the Hasmonean lineage, who died in 37

BC, executed by Mark Antony. According to Raymond, Mary was also of Herod's

lineage, that is, descended from the two most recent royal lineages in Judea.

But if that was the case, she was not that young when she gave birth to Jesus,

as she must have been almost 40.

No matter who Mary's parents were, there is no doubt in the Gospels that she was

the mother of Jesus. Some scholars, especially religious ones, believe that Mary

remained a virgin until her death, and that Jesus' siblings mentioned in the

gospels were not her children. Other scholars, on the other hand, believe that

it appears from Matthew that Mary did not remain a virgin. It is especially this

phrase in Matthew that is used as an explanation: "But he did not consummate their

marriage until she gave birth to a son. And he gave him the name Jesus".

(Matt. 1.25). The way it is worded seems to indicate that he certainly did

consumate the marriage after the birth of Jesus, and that would be the most

natural thing, considering the attitude of the time towards marriage and

children.

Mary Magdalene

If Mary, the mother of Jesus, is the most important Mary in the Gospels, Mary

Magdalene must enter as a close runner up, if she is not actually the most

important.

The

penitent Magdalene, Domenico Tintoretto, around 1600, Musei Capitolini, Rome The

penitent Magdalene, Domenico Tintoretto, around 1600, Musei Capitolini, Rome

The nickname Magdalene is usually interpreted as if she came from a town called

Magdala. However, such a town has never existed in Palestine. The town in

question might be Migdal Nunaiya, which was located about 15 southwest of

Capernaum on the Sea of Galilee. The name meant "A tower of fish" and the town

was famous for boat building and processing of fish, eg salting. According to

Josephus, who lists the towns of Galilee, the city had up to 40,000 inhabitants

when the war broke out in 66, which is probably an exaggeration.

It is therefore

not likely that Mary was named after a town that presumably did not exist, but

she could of course have been named Maria Migdal, to indicate that she was a "tower"

that towered over the other disciples in her wisdom or her belief in Jesus or

something like that. This is how many scholars interpret the nickname, ie almost

as "Mary the Great", and this can be argued, not least because of descriptions

in a number of apocryphal writings. However, it is difficult to see from a

linguistic point of view how Migdal could change to Magdalene. Another

indication that she was hardly named after a city is the way the nickname is

given in the gospels. Other people, who are named for their geographical

affiliation, are always called nn of yy, eg Joseph of Arimathea, Simon of

Cyrene, Lazarus of Bethany and so on. Moreover, place names in the Gospels are

always associated with men, not women. In the Gospel of Luke (Luke 8.2), Mary is

referred to in this way: "Mary (called Magdalene) from whom seven demons had

come out;" and King James' Bible has: "Mary called Magdalene, out of whom

went seven devils," and everywhere else in the Gospels where the wording "was

called" is included, it is a nickname, not a geographical reference, eg Jesus,

who was called Christ, Simon, who was called the Zealot, Judas, who was called

Iscariot, etc. It has also been argued that if Mary came from a place called

Magdala, her name in Greek should have been Magdalaia, not Magdalene.

Laurence

Gardner directly states "Magdalene was a distinction, not a surname and had

nothing to do with a place." (Laurence Gardner, The Magdalene Legacy) and

Margaret Starbird, American feminist, believe that the nickname was chosen

deliberately, so that according to Jewish gematria (a system that assigns

numerical values to letters), it gets the number 153, which was the number of

fish that Jesus captured after his resurrection and a sacred number for Greek

mathematicians. (Margaret Starbird, The Feminine Face of Christianity).

Years ago, when

I first got interested in this subject, I read a lot of books about Jesus as a

historical person. In one of these (in my notes I have unfortunately not noted

which one, but when I find it I will reveal the source), I read another

interpretation of the nickname. The author believed that Magdalene was a distortion of

the aramaic word "maggadla", which menat "weaver", and it

was a term for a very specific person, not a weaver in general. According

to my unfortunately forgotten source, "maggadla" was the title of the woman who wove the

sacred veil that separated The Holy Place from The Holy of Holies in the Temple

in Jerusalem. If this is correct, it would first of all place Mary Magdalene in

Jerusalem or the surrounding area, and not in Galilee, and it would place her in

the upper class, as it was from the upper class that those who served in the

temple was chosen. This fits very well with the fact that most of Jesus' other

female followers belonged to the upper class, and as I have already mentioned in

the article about Jesus' parents, see above, Jesus' parents probably also

belonged to this class of people.

Like it was the

case with Mary, mother of Jesus, the gospels do not tell much about Mary

Magdalene. From the gospels of Mark and Luke we get the impression that she was

relatively wealthy, (Mark 15.40-41 and Luke 8.1-3). From the latter it appears

that Mary Magdalene (and other women) had their own means, which women usually

didn't have at the time, unless they had inherited before getting married,

or had inherited from a deceased husband. In King Jesus, the novel by Robert

Graves, which he claimed was based on sources that he unfortunately don't

disclose, Mary Magdalene is an elderly, wealthy widow, and aquaintance of both

Mary, and her parents.

Mary Magdalene appears once in Luke in connection with the quote mentioned

above. In this passage in the gospel it appears that Mary is a woman from whom

seven demons had come out. This episode leads some to believe that she has been

cured of some kind of disease, but in fact no one knows exactly how to interpret

the "seven demons". Apart from this episode, Magdalene appears only in

connection with the crucifixion and resurrection, and after this she is no

longer mentioned in the Gospels. In connection with crucifixion and

resurrection, she played a major role though. She was present at the cross and

she was one of those few for whom Jesus appears soon after being resurrected.

She plays a similar or even greater role in many of the apocryphal writings,

such as the Gospel of Mary* and the Gospel of Philip. When Mary is mentioned in

the Gospels with other women, she is always mentioned first - even though Jesus'

mother is in the group, just as Peter is always mentioned first among the male

disciples. This seems to indicate that Magdalene, was the most important among

the women.

* It should be mentioned that in the Gospel of Mary the nickname is never

mentioned, so it is not a given thing that this gospel is about Magdalene,

but most scholars assume that it is.

In 591, Pope Gregory the Great wrote that Mary was a prostitute, and this

quickly became a well-established fact, although no contemporary sources mention even

with a single word. In 1969, the interpretation was rejected by the

Vatican under Pope Paul VI. From the tenth century, Magdalene was given the

title of the Apostle of the Apostles and some modern scholars believe that she

was the leader of a faction of the early Christian movement that advocated

female leadership.

Mary of Bethany

In the previous paragraph about Mary Magdalene I mentioned that geographical

nicknames nn of xx were always associated with men in the gospels, and now I

introduce Mary of Bethany? But just to make this clear, this Mary is never

identified as Mary of Bethany anywhere in the gospels. The nickname is used by

modern and not so modern scholars only to distinguish her from other Marys in

the gospels, like for instance Mary Magdalene.

Christ in the House of Martha and

Mary, Jan Vermeer, around 1555, Scottish National Gallery

Mary was the

sister of Martha and Lazarus and lived in Bethany, a little more than a mile

outside Jerusalem. And that's about all we know about her. One Mary is

also mentioned in the stories about the anointment of Jesus, but unfortunately,

the scriptures do not tell much and are therefore open to interpretation.

The whole story

about the anointment has actually led some scholars to believe that Mary Magdalene and

Mary of Bethany are one and the same, but of course this cannot be the case for

those who also insist that Magdalene means "of Magdala" or Migdal. Mary can't come

from two different towns. If, on the other hand, it is correct that the name,

Magdalene, is a derivation of the "weaver", it may well be correct that a person

who worked for the temple lived in a town less than 1.5 miles from Jerusalem.

But let me take a closer look at this discussion. The linking of the two Marys

is done because the verses in the Gospels that deal with the anointing

of Jesus, so let me take a closer look at what they actually say. According to

Luke, the anointing takes place as follows: "When one of the Pharisees

invited Jesus to have dinner with him, he went to the Pharisee’s house and

reclined at the table. A woman in that town who lived a sinful life learned that

Jesus was eating at the Pharisee’s house, so she came there with an alabaster

jar of perfume. As she stood behind him at his feet weeping, she began to wet

his feet with her tears. Then she wiped them with her hair, kissed them and

poured perfume on them."* (Luke 7.36-38). This takes place after Jesus

raised a widow's son in the city of Nain in Galilee and after he has been in

contact with messengers from John the Baptist. This again leads some to believe

that this must have happened somewhere in Galilee, but the episode is described

without connection to those before and after, so it may just as well have

happened somewhere else, for example in Judea. Not least because the synoptic

gospels tend to place most of Jesus' ministry in Galilee, although he must have

also spent a lot of time in Judea (cf. the Gospel of John and the fact that many

of the people he knew, lived in Judea). In the above episode, not a word is

mentioned that the one who anointed Jesus was called Mary (or any other name for

that matter), but still it is probably this episode, which together with the

passage quoted above, also from Luke, that seven demons had been driven out of

her, that has been the basis of the opinion that Mary Magdalene was a prostitute.

This opinion became widespread in the sixth century under Pope Gregory the Great,

but it thrives to this day without any evidence for it in the New Testament. The

only name Luke gives is the name of the Pharisee whose name is Simon. Luke

himself mentions Mary Magdalene in chapter 8 verse 2 as mentioned above, but he

does not connect her in any way with the woman who anointed Jesus.

* This quotation is taken from Online Bible from Biblica, The Bible Society. The

translation in King Jemes' Bible is a bit different.

Mark also knows the episode, but contrary to Luke, he knows that it took place

in Bethany: "While he was in Bethany, reclining at the table in the home of

Simon the Leper, a woman came with an alabaster jar of very expensive perfume,

made of pure nard. She broke the jar and poured the perfume on his head."

(Mark 14.3) We must assume that Simon the Leper was the same Simon who was a

Pharisee in the story in Luke. The difference between the two stories, in

addition to the geographical location, is that in Mark it is Jesus' head that is

anointed, not his feet, and we are told that the ointment that was used was very

expensive - not exactly something that suggests that the woman who was anointing

Jesus was a poor prostitute. However, we must still believe that it is the same

episode that is being referred to. John knows the name

of the woman who anointed Jesus. It was Mary from Bethany (and she was certainly

not a prostitute or anything like that). Strangely, John already tells in

chapter 11 that Mary was the woman who anointed Jesus, while he first tells

about the anointing itself in chapter 12, so either the two chapters have been

switched around or the remark "This Mary, whose brother Lazarus now lay sick,

was the same one who poured perfume on the Lord and wiped his feet with her hair"

(John 11.2) is an addition from later editors who knew the next chapter. In

chapter 12, John relates: "Six days before the Passover, Jesus came to

Bethany, where Lazarus lived, whom Jesus had raised from the dead. Here a dinner was given in Jesus’ honor. Martha served, while Lazarus was among those

reclining at the table with him. Then Mary took about a pint of pure nard, an

expensive perfume; she poured it on Jesus’ feet and wiped his feet with her hair.

And the house was filled with the fragrance of the perfume." (John 12.1-3).

Here it is obvious that the anointing took place shortly before Jesus' entry

into Jerusalem and after Jesus had raised Lazarus from the dead. Neither in John

are there any indications that Mary from Bethany was the same as Mary Magdalene.

But whu annoint Jesus' feet? The normal was to annoint the head. Luke and John

agree that the woman annointed the feeet, while Mark tells that she annointed

Jesus' head! According to Luke she shed tears on Jesus' feet and wiped them of

with her her before annointing them. Mark knows nother about any tears an

neither does John, but he knows that she wiped Jesus' feet with her her, so

maybe there have been a mix-up here. The woman washed Jesus' feet as it was a

normal favor to bestowe on honored guests in those days. Then she dried his feet

with her hair (or something else). Finally she annointed him - on his head as

was custom, but Luke and John got the two acts mixed up.

Those who argue

that the two Marys were the same person often use a circular argumentation. "Jesus

was anointed by a woman who was a sinner" (Luke). "Mary Magdalene was a woman

whom seven demons had cast out" (Luke) (That seven demons had been cast out of

her is not necessarily the same as that she was sinful, but I will let that one

slip). "The anointing took place in Bethany" (Mark and John). "The woman who

anointed Jesus was called Mary" (John). Therfore to prove that Mary of Bethany

was the same person as Mary Magdalene, it is assumed that the two were the same

person! Above I mentioned Gregory the Great (Gregory the First, pope between 590

and 604). Perhaps it was, in fact, he who also was the man behind the tradition

that Mary Magdalene and Mary of Bethany were one and the same person. Gregory

wrote in a commentary on the Gospel of John in 591 (Commentary number 33): "She,

whom Luke calls a sinful woman, whom John calls Mary, we believe, is the Mary

from whom seven demons were cast out according to Mark. And what then do these

demons symbolize, if not all vices? Here the pope equates the two Marys and at

the same time makes Mary a sinful woman. Incidentally, he goes on to clarify

what a sinful woman does with the ointment: "It is clear brethren that the woman

formerly used the ointment to perfume her flesh (!!) by forbidden deeds."

The "battle"

between scholars of who Jesus was married to - if any - is primarily "fought"

between proponents of Mary Magdalene and proponents of Mary from Bethany, but

before I delve into this "battle", I will just take a brief look at the other

Mary's mentioned in The New Testament.

Mary,

mother of James and Joses and Mary, wife of Clopas

In the account of the crucifixion in the Gospel

of Mark, it says: "Some women were watching from a distance. Among them were

Mary Magdalene, Mary the mother of James the younger and of Joseph" (Mark

15.40). In connection with the resurrection, Mark has "When the Sabbath was

over, Mary Magdalene, Mary the mother of James, and Salome bought spices so that

they might go to anoint Jesus’ body" (Mark 16.1). Matthew has the following:

"Among them were Mary Magdalene, Mary the mother of James and Joseph, and the

mother of Zebedee’s sons" (Matt. 27.56), and in connection with the

resurrection is mentioned "After the Sabbath, at dawn on the first day of the

week, Mary Magdalene and the other Mary went to look at the tomb. (Matt.

28.1). Luke does not mention any names in connection with the crucifixion, but,

does mention a Mary in connection with the resurrection: "When they came back

from the tomb, they told all these things to the Eleven and to all the others.

It was Mary Magdalene, Joanna, Mary the mother of James, and the others with

them who told this to the apostles" (Luke 24.9-10).

Maria Magdalene has already been discussed so no more about her, at least not

for now. All three synoptic gospels mention another Mary. She is the mother of

James (The Younger or The Lesser) and Joses in two of the Gospels and only the

mother of James in Luke and in one quote from Mark. Interestingly, none of the

synoptic gospels mention Jesus' mother on this occasion. John, on the other hand,

does: "But at the cross of Jesus stood his mother, his mother's sister, Mary

the wife of Clopas, and Mary Magdalene" (John 19:25). John is usually

reasonably well informed about the events in Judea, and not least at the

crucifixion. There is therefore reason to believe that Jesus' mother was also

present, but why do the other gospels not mention her?

Some scholars believe that they actually do,

referring to Matthew: "Isn’t this the carpenter’s son? Isn’t his mother’s

name Mary, and aren’t his brothers James, Joseph, Simon and Judas?" (Matt.

13:55). So Jesus has four brothers, two of whom are named James and Joseph

(Joses). It leads some to believe that the Mary in question is actually the

mother of Jesus. But if that was the case, why not identify as such instead of

identifying her as mother of his brothers? If this Mary is actually Jesus'

mother, James the Little is the same as James the Righteous. This James, who was

actually the brother of Jesus, became the leader of the congregation in

Jerusalem when Jesus died. The Church Father Hieronymus believed (around the

year 400) that "brother" should actually be understood as "cousin", and that

those referred to as Jesus' brothers were in fact his cousins, and sons, not of

"Virgin Mary", but of Mary, Clopas' wife. Since some also believe that James the

Younger was the son of Clopa's wife, James the Righteous became equated with

James the Younger. But this causes a new question, for how was Mary, mother of

Jesus, related to Mary, wife of Clopas? Hegesippus, who lived at the end of the

second century, wrote that Clopas was the brother of Joseph and that his wife

and Jesus' mother were therefore sisters-in-law. Now there is actually doubt as

to whether the Greek text should be translated as Mary, Clopas 'wife or Maria,

Clopas' daughter, but in any case, the relationship was through marriage.

The Entombment of Christ,

Michelangelo Caravaggio, 1602, Vatican Pinacoteca. The woman with her arms stretched upwards is Mary, Wife of Clopas. In front her Virgini Mary (left) and

Mary Magdalene (right). The man carrying Jesus's legs is Nicodemus, and the man

carrying his upper body (almost hidden) is John, son of Zebedee.

Other scholars have a different interpretation,

which is based on the vague wording in John: "...his mother, his mother's

sister, Mary the wife of Clopas, and Mary Magdalene". It is actually not

clear whether this passage mentions three women or four. Thus, some believe that

"Mary, Clopas' wife" is an extension of "his mother's sister", and that the two

Marys were sisters. As a justification, they state that it would be strange to

mention "his mother's sister" without naming her when the others are named.

Others believe that "his mother's sister" and Mary, Clopas' wife "must be two

people, as it is not likely that two sisters had the same name. Actually there

are elements that in my opinion speak for both views. Today, it would be strange

but not impossible if two sisters had the same first name. (I actually know two

sisters who share first name, and thus are known to everyone by their middle

names.) It would also seem strange if both Hegesippus was right and Clopas was

the brother of Joseph, while his wife was the sister of Mary. The latter,

however, occurs occasionally and, for example, in the nineteenth century, it was

also common in the Western world for two or more siblings to marry siblings of

each other's spouses, and even today it happens. Two of my female relatives (sisters)

are married to two brothers. Another point of view is that "the second Mary" was

the mother of the apostle James, who was called 'James, the son of Alphaeus'. If

so, she must either have been the daughter of Clopas or Alphaeus and Clopas have

been two names for the same person. Proponents of this theory argues that both

names could be garbled versions of the Aramaic name 'Hilfai". Or Alphaeus, which

actually means "Successor" could be a nickname for Clopas.

However, I don't think it needs to be that

complicated. First of all, I am convinced that 'Mary, mother of Jesus' and

'Mary, mother of James and Joses' were two different people. Both Mary, James

and Joseph were quite common names, and other people in the New Testament are

known by these names. 'Mary, the mother of Jacob and Joses', is in my opinion

probably the same one whom John calls 'Mary, Clopa's wife'. I also believe that

this Mary is the sister of the "Virgin Mary". It would also explain the somewhat

shallow and casual "the other Mary" in Matthew, if the two Marys were

sisters, and it was not the mother of Jesus that he was referring to. And if

they were actually sisters it would explain why the Synoptic Gospels mention

three women, while John mentions four. Finally, a family relationship between

the two would explain why both had children who had the same names, as the

tradition was that you named your children after parents and grandparents, who

would be shared between the two women. This is also supported by the apocryphal

Gospel of Philip, which states: "There were three who always went with the

Lord: Mary, his mother and her sister, and Magdalene, who was called his

companion. His sister and his mother and his companion were all named Mary."

However, the confusion is not lessened by the fact that first his mother's

sister is mentioned, but in the next sentence his own sister is mentioned, but

this is most likely a writing error from whoever wrote down this gospel. But it

is of course possible that Jesus' own sister was named Mary after their mother,

and that Mary's sister was named something else.

The Gospel of Matthew is the only one that

mentions the mother of the sons of Zebedee, while Mark alone mentions Salome.

Neither Luke nor John mentions these two women, but they are usually considered

to be the same person, so that the mother of the sons of Zebedee was named

Salome. Some suggest (mostly those who do not believe that two sisters can have

the same name) that it was Salome who was the sister of Jesus' mother in John,

and that can't be rejected either. Some traditions call Salome 'Mary Salome',

and believe that she was the mother of Jacob and Joses. To make it even more

muddy, the sons of Zebedee were named James and John, so here too a James is

mentioned. A tradition from the beginning of the second century, ie quite early,

namely The Greek Gospel of the Egyptians, suggests, however, that Salome was

childless, and if so she can not be the mother of the sons of Zebedee.

The so-called "Secret Gospel of Mark"* also

mentions Salome: "And the sister of the young man whom Jesus loved was there

with his mother and Salome, but Jesus would not receive them." This passage

in this apocryphal and now disappeared part of Mark, known only from quotations

in letters from the Church Fathers, deals with the resurrection of Lazarus, who

must thus be "the young man whom Jesus loved" and his sister must be either

Martha or more likely Mary from Bethany. Who their mother was is not known,

although I have an idea. And unfortunately, it also does not shed light on who

Salome was, except that she must have belonged to the inner circle around Jesus.

The Gospel of Thomas suggests that Salome was also wealthy, as Jesus at one

point shared "her bench" during a meal that must have taken place in her house,

as she was clearly not just lying on the bench, but owning it. According to the

Gospel of James, also known as the Protoevangelium of James, Salome was present

outside the stable when Jesus was born, but did not believe that Mary was a

virgin when she was told by the midwife that now the child was born.

* I will get back to this "gospel" in another

article at a later time.

Another apocryphal text, "The Book of the Resurrection of Jesus Christ," said to

have been written by the apostle Bartholomew, makes the confusion surrounding

Salome total. This apochryphical gospel says about those who were at the tomb: "Among

them were: Mary Magdalene, Mary the mother of James, whom Jesus delivered from

Satan; Mary who served him, Martha her sister, Johanna, who renounced the

marriage bed and "Salome who tempted him." Once again Mary, mother of Jesus

is not mentioned, but in return the "book" mentions both Mary of Bethany and her

sister Martha. Also Johanna (mentioned nowhere else in any gospels in

conncection with the execution and resurrection), who is apparently divorced or

had left her husband to follow Jesus, and also Salome, "who tempted him". How

she "tempted him" it is not clear. On the other hand, in this writing it is not

Magdalene who was torn out of Satan's clutches, but instead Mary, James' mother!

Unless of course Mary Magdalene was the mother of the said James!

Before getting to the remaining two Marys, I'd better summarize, as the above

probably got a little confusing in the end :-), so here is what I believe.

Mary, mother of Jesus, Mary Magdalene, Mary of Bethany and Mary, mother of James

(and Joses) are all different women. The latter, however, is identical with

Maria, Clopas' wife or daughter. Salome, may well have been named Mary as well,

but I doubt it. She is probably the mother of the sons of Zebedee. I mentioned

above that I had an idea about who could be the mother of Lazarus, Mary and

Martha, and although I do not have a single evidence of that, I believe it may

have been Mary Magdalene. She was wealthy like them, her husband is never

mentioned, so she was probably widow, and in my opinion, she belongs in Judea,

not Galilee, as many otherwise think. If she was an aquaintance of Jesus'

parents it would also account for Jesus knowing her as well as her children, and

if she was a widow it could explain how she could travel together with Jesus.

Mary, mother of John Mark

and Mary from Romans

Mary, mother of John Mark, is only mentioned in Acts of the Apostles. Herod has

arrested John's brother James and had him executed, and now Peter has also been

arrested. The James mentioned is usually assumed to be the son of Zebedee, but

this is not explicitly stated. Peter escaped with the help of an angel and in

12.12 he goes to Mary's house: "When this had dawned on him, he went to the

house of Mary the mother of John, also called Mark, where many people had

gathered and were praying" (Acts 12.1-2) That's all we hear about this

specific Mary. Her son is mentioned again later in Acts, namely in 12.24-25,

where it is stated: "But the word of God continued to spread and flourish.

When Barnabas and Saul had finished their mission, they returned from Jerusalem,

taking with them John, also called Mark." Saul is the one who later became

known as Paul and Joseph Barnabas, was one of Paul's companions on many journeys.

Interestingly, Barnabas' nickname can be translated as "son of the prophet",

although other translations are also possible. Later Acts has (about another

travel): "Barnabas wanted to take John, also called Mark, with them, but Paul

did not think it wise to take him, because he had deserted them in Pamphylia and

had not continued with them in the work. They had such a sharp disagreement that

they parted company. Barnabas took Mark and sailed for Cyprus, but Paul chose

Silas and left, commended by the believers to the grace of the Lord" (Acts

15.37-39). The story of John who left Paul and his retinue in Pamphylia can be

read in Acts 13.13, where John Mark is only called John.

John Mark is considered by many to be the same

Mark who was the author of the Gospel of Mark, but there is no evidence of this,

except for the name, and it is not obvious that this should be the case, as John

Mark traveled with Paul, while the author of the Gospel of Mark by most scholars

is believed to have been Peter's companion. Some believe that John Mark is the

same as Mark, cousin of Barnabas, mentioned in the letter of Colossians: "My

fellow prisoner Aristarchus sends you his greetings, as does Mark, the cousin of

Barnabas. (You have received instructions about him; if he comes to you, welcome

him.)" (Col. 4.10) and in the Epistle to the Philemon, which reads: "Epaphras,

my fellow prisoner in Christ Jesus, sends you greetings. And so do Mark,

Aristarchus, Demas and Luke, my fellow workers." (Philem. 1.23-24).

Already Hipolytes, who died in 235, believed that there were three different

persons, and I certainly agree that John Mark was not the same as the author of

the Gospel of Mark, but I will return to that later in an article on the origin

of the scriptures. Neither was he a likely cousin of Barnabas, who was from

Cyprus, while John Mark was from Jerusalem.

Actually, it is not - at least in this connection

- important who John Mark was, since this is about his mother. There is no doubt

that she was one of the first members of the Christian congregation in

Jerusalem, and that she must have been relatively wealthy, is also quite certain,

as she owned a house large enough for many to be gathered inside, and large

houses in or just outside Jerusalem, were not cheap then either. In addition,

she has at least one maid or slave girl in the house. As she herself owned the

house, it probably indicates that she was a widow, but she may also have been

unmarried and inherited the house from parents.

The events surrounding Peter's arrest took place around 41 or 42, so Mary could

easily have been one of the women who traveled with Jesus 6 to 10 years earlier,

and who is mentioned in the Gospels without being named. She may theoretically

also have been one of the above discussed Marys, but if that is the case, it is

difficult to say which one. Some of those who maintain the "cousinship" between

John Mark and Barnabas believe that she was the sister of one of Barnabas'

parents, see for example http://www.bibarch.com. However, the WebBible

Encyclopedia makes her a sister of Barnabas himnself (https://christiananswers.net/dictionary/mark.html).

The fact that Mary provided a home for the Christians must have meant that she

either had courage beyond the ordinary, since Herod Agrippa was pursuing them at

this very time. James, Zebedee's son had just been executed, Peter had been

arrested and yet she keeps an "open house" to the Christians. However, it is

also possible that she has had such good relationships that Herod would not or

could not take any action against her. Peter asks her to send a message to

James, Jesus' brother, who was the leader of the congregation, so he was not

present in the house when Peter arrived, but Mary must have known him as well.

The fact that Peter, after his escape, went directly to her house suggests that

she was close to the inner circle of the Christian congregation, so she might

well have been one of the previously mentioned Marys. Here I believe most in

Mary, Clopa's wife, but if Magdalene was the "weaver" she would have been

wealthy and live in or in the close vicinity of Jerusalem, and could easily have

a son. However she may also have been a not previously mentioned Mary.

This undoubtedly applies to the last Mary, namely the one mentioned in Romans

16.6, where it says, "Greet Mary, who worked very hard for you." A few

sources believe that she is the same as Mary, mother of John Mark, but this is

rejected by most scholars. The letter is one of those that most people agree was

actually written by Paul himself in the mid-50s. The wording of the letter

suggests that the said Mary herself lived in Rome, since the Romans were to

greet her, and Mary, the mother of John Mark, lived in Jerusalem in the early

40s, so she might have managed to travel to Rome and settle there, perhaps

because she was persecuted for her help to the Christians, but probably not.

Some believe that Paul had met Mary in Greece, but that she and other Christians

had now moved to Rome. In any case, this Maria has probably little to do with

the others mentioned.

So after going through all the different Marys

mentioned in the New Testament, let me return to the question of Jesus possible

bride.

If Jesus was married, then who was his bride?

Since Dan Brown published the novel "The da Vinci

Code", many of the readers of this novel will probably answer the question in

the header by saying Maria Magdalene, and

there are many others, even scholars who agree. On the other hand, many of those

who argue that Jesus never married, claims that he could not have been married

to Magdalene. But even if he was not married to her, he could have been married

anyway. Maybe with one of the other women mentioned in the Scripture, maybe with

a woman who is not mentioned at all. Although it is said that Simon Peter, the

other apostles, and Jesus' brothers were married, none of their spouses are

mentioned by name. On the whole, relatives are mentioned only very peripherally.

For example, we learn about Joanna, who followed Jesus, that she was married to

Chuza, an official at Herod's court. We learn about Simon Peter, that he has a

mother-in-law, and that some of the apostles are brothers, and we hear from time

to time about individual parents, but otherwise family relationships are

not often mentioned in the Gospels.

As mentioned above there is a "battle" between

those who believe that Jesus was married to Magdalene and those who believe that

he was married to Mary from Bethany, and there are some who try to settle the

schism by making the two Marys one and the same person. I have already argued

above that I don't believe that was the case, so I will not repeat that here,

but let me turn to the gospels anyway:

"Now a man named Lazarus was sick. He was from