The sad fate of a young girl

In this story as well as in the previous one, I stay in England but about 400 years later than the story of the shipwreck. That was a story, about a shipwreck that caused a civil war some years later. The present story is about the faith of a young girl. A faith caused by a civil wat that took place several years before. NB! All pictures are from commons.wikimedia.com.

Background - the civil war

From around 1455 to 1487 a civil war was fought in England. It is said that it was not really a civil war, but rather a war of the nobility, but in the end, the soldiers that fought and were killed were ordinary people, not noblemen. The war I'm referring to is known as The War of the Roses. It was fought between supporters of The House of Lancaster and supporters of The House of York. The name War of the Roses was due to the two parties each having a rose in their coat of arms. A red rose for York and a white rose for Lancaster. Both houses were royal as they both descended from Edward III. The House of Lancaster descended by John of Gaunt, 1. Duke of Lancaster and third son of king Edward. The House of York descended by Lionel of Antwerp, Edwards second son and Edmund of Langley, 1st Duke of York and Edwards fourth son.

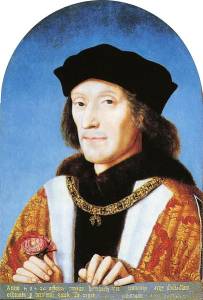

In 1399 The House of Lancaster came to the English throne, when John of Gaunt's son Henry of Bolingbroke, became king under the name of Henry IV after having arrested his first cousin, King Richard II. Richard was sent to prison, where he died under mysterious circumstances. Henry IV was succeeded by his son, Henry V, but he died while his son, Henry VI was still a child, and Richard, Duke of York laid claim to the throne, which resulted in troubles with the Lancaster Clan and ensuing skirmishes. The first major battle took place in 1455 and this is regarded as the beginning of The War of the Roses. As this war is only indirectly connected to my story I will jump the end of the war. In 1483 Richard of Gloucester mounted the throne under the name Richard III (known from Shakespeare's play - the one with the famous line, "My kingsom for a horse") . Two years later Richard was defeated at the battle of Bosworth Field. Richard was killed in the battle, and thereby became the last king of The House of York, and also ending the Plantagenet dynasty, that had ruled England since Henry II came on the throne in 1154. The victor of the battle was a distant relative of the Welsh branch of The House of Lancaster, who somehow had inherited his clan's claim for the throne. His name was Henry Tudor and he was crowned as Henry VII. Thus ended The War of the Roses on the whole, even if members of the York family cotinued to rebel at intervals for the next 12 years until 1497.

Henny VII was the first

king of The House of Tudor, and his reign was the beginning of what later became

know as The Tudor Period. Henry had tried to unite the clans of York and

Lancaster by marrying Elizabeth of York, a daughter of Edward IV and a niece of

Richard I II. Henry's mother was Margaret Beaufort, Countess of Richmond and

Derby. She was married to John de la Pole when she was only about one year old (some

say that the marriage took place later, when she was seven), but the marriage

was annulled, and some years later, in 1455 she married Henry's father, Edmund

Tudor. One year later, at the age of 13 she gave birth to Henry. His father had

died three months before he was born and Margaret was a very young widow. Henry

VII himself had several children. Among these were Arthur, Prince of Wales who

died at the age of 16, but even so managed to get married to Catharine of Aragon.

Another son was Henry who became Henry VIII, a daughter was Mary, who became

Queen of France by her marriage

to Louis XII. When Louis died only three months

after the wedding, she married Charles Brandon, 1st Duke of Suffolk later that

same year. Among Mary's children with Suffolk, was Frances Brandon, who married

Henry Grey, Marquis of Dorset in 1533. Through this marriage, Henry Grey gained

the title Duke of Suffolk, as there were no male heirs to the title. Keep this

family in mind, as not least Frances Brandon played a part in what later would

happen.

II. Henry's mother was Margaret Beaufort, Countess of Richmond and

Derby. She was married to John de la Pole when she was only about one year old (some

say that the marriage took place later, when she was seven), but the marriage

was annulled, and some years later, in 1455 she married Henry's father, Edmund

Tudor. One year later, at the age of 13 she gave birth to Henry. His father had

died three months before he was born and Margaret was a very young widow. Henry

VII himself had several children. Among these were Arthur, Prince of Wales who

died at the age of 16, but even so managed to get married to Catharine of Aragon.

Another son was Henry who became Henry VIII, a daughter was Mary, who became

Queen of France by her marriage

to Louis XII. When Louis died only three months

after the wedding, she married Charles Brandon, 1st Duke of Suffolk later that

same year. Among Mary's children with Suffolk, was Frances Brandon, who married

Henry Grey, Marquis of Dorset in 1533. Through this marriage, Henry Grey gained

the title Duke of Suffolk, as there were no male heirs to the title. Keep this

family in mind, as not least Frances Brandon played a part in what later would

happen.

In 1509 Henry VIII got on the throne, and he married the widow of his late

older brother, Catherine of Aragon. She was a very good friend of Frances

Brandon Grey. Henry sired a daughter, Mary, with Catherine, but no sons. He

started an affair with one of the queens maids of honor, Mary Boleyn, but later

fell in love with Mary's sister, Anne Boleyn. This love affair ultimately led to

his divorce from Catherine. Unfortunately they were both catholics, and the

pope wouldn't sanction a divorce, even if Henry pleaded that the marriage was

not legal in the first place, as Catherine had been married to his brother.

This led to Henry's break of from the catholic church. He established The Church of

England with himself as head of the church and independent of the Holy See. He

divorced Catherine and married Anne in 1532. Neither did this marriage produce

any male offspring, but he had another daughter, Elizabeth. Anne Boleyn got

pregnant with a male child though, but miscarried when Henry was badly injured in

a tournament. At this time Anne had become very unpopular among many nobles

because of her arrogant behaviour. Among her enemies were The Duke of Suffolk

and her own uncle, The Duke of Norfolk. Rumors were spreading about Annes

infdelity, and accusations of conspiracy and witchcraft were made against Anne.

At that time, Henry had entered into a relationship with one of Anne's ladies in

waiting, Lady Jane Seymore. She moved into the royal appartments, Annes

relatives were removed from office, and on May 17th, 1536 they were executed.

Two days later, on May 19th, Anne herself followed to the saffold them and was beheaded on

Tower Green within the walls of Tower Castle.

After Anne's execution Henry married Jane Seymore, and with her he finally sired

a son, Edward in 1537. Unfortunately Queen Jane died of complications after

childbirth. Henry married three times after Jane. First to Anne of Cleves but

that marriage was dissolved soon after. Then to Catherine Howard a cousin of Anne Boleyn

and one of her former maids of honor. Unfortunately Cathgerine was not very

faithful, and even more unfortunately Henry found out and had her two suspected

lovers, Francis Dereham and Thomas Culpeper executed on December 10th 1541.

Catherine was imprisoned in Syon Abbey in Middlesex, and on Februray 13th 1542

she followed in her lovers footsteps. On the evening before her execution,

the execution block was brought to her rooms at her own request,, and she practised all night on how

to place her head on the block elegantly! Immediately after Catherine's body had

been removed from the scaffold, her lady in waiting, Jane Boleyn, wife of Anne

Boleyns brother was also beheaded. Both of them were buried in the chapel of St.

Peter ad Vincula inside the tower, where also Anne Boleyn and her brother George

was buried. Jane Boleyn herself is worth a story and maybe I will tell that

sometime. She got rid of her husband by testifying that he had had an affair

with his own sister, Anne and that he might be the father of the miscarried

foetus, not Henry. The queen was 18 at the time of her execution and Jane Boleyn

was 36. By the way, it was never proven that Catherine had actually been unfaithful to

the king, but Henry was not one to wait for proof, when he was angry!"

The last marriage of Henry VIII was to Catherine Parr. She was the only queen to outlive the king and the first queen to achieve the title Queen of Ireland. She was twice a widow of 31 when she married Henry. Her first two husbands had died early in the marriage. Catherine Parr re-established a good relationship between Henry and his two daughters, and she had a very good relationship with all his three children. Henry died in 1547 and was buried in a chapel at Windssor Castle, next to Jane Seymore, the queen who gave him a son. Catherine Parr died one year later after yet another marriage. No other English queen was married so many times as Catherine Parr.

A male heir

Henry VIII was very anxious to

sire a male heir, which was one of the reasons

for the frequent change of queens. It was also the cause of his

conflict with

the papacy in Rome. When the Pope wouldn't allow him to divorce Catherine of Aragon,

the Pope prevented Henry from having a male heir, and that caused Englands'

break up with

the Catholic Church in 1534.

conflict with

the papacy in Rome. When the Pope wouldn't allow him to divorce Catherine of Aragon,

the Pope prevented Henry from having a male heir, and that caused Englands'

break up with

the Catholic Church in 1534.

But why was Henry so keen to get a male descendant who could inherit the thron

? Unlike many European royal houses who lived the by the old Frankish law, called

the Salian

law under which women could not inherit the throne, England actually had female

succession, in the sense that if there were no male heirs, the throne would go to

a female heir. And that was exactly what Henry would prevent! Not because he had anything against women - he personally made his daughters

Mary and Elizabeth heirs to the throne after his son Edward when he was "reunited"

with the two girls after his last marriage. His problem was simple fear of what might happen if

there were only female heirs to the throne. It was exactly what had happened in

the 1100s when William Adelin, Henry I's son died in the said shipwreck, and

there were no other male heirs. This had led to an 18-year long civil war, and

at Henry's time, only 50 years had passes since

England had suffered another 30 year long civil war. Henry feared what such a civil war would do to the country.

And besides he feared that

a female heir would marry a foreign ruler and thus surrender England's

independence.

Now, however, he got his son Edward , who was the first heir and in

The Third Succession Act he named his two daughters as second and third heir

after Edward, and if none of

these left heirs, the throne would go to descendants of his younger sister,

Mary, former Queen of France. At the same time he reserved the right, however, to alter the succession

in a later will. As he now had a son to succeed him, he saw no reason make any changes to the

succession act. So when Edward took the

throne as Edward VI the Third Succession Act still applied. Had Henry known what

was going to happen after his death he might have changed the sucession in his will

anyway.

The legacy of Edward

Edward was born in 1537 and six years old he was betrothed to the

seven month old Mary of Scotland. When Henry VIII died and Edward was crowned king, he was nine years old.

As he wasn't old enough to run the country, this was

ruled by a "Regency Council", which was at first led by the

king's uncle, Edward Seymore, 1st Duke of Somerset, but from 1549 it was led by

John Dudley, 1st Earl of Warwick who two years later was appointed first Duke

of Northumberland. In the beginning of Edwards "reign" , the country was plagued by

riots and an expensive war with Scotland, which ended with defeat, and the British had to

give up not just Scotland, but also possessions in northern France to gain peace.

Under Edward, who was very interested in religious matters, Church of England

developed in a more Protestant direction than under his father.

Edward was born in 1537 and six years old he was betrothed to the

seven month old Mary of Scotland. When Henry VIII died and Edward was crowned king, he was nine years old.

As he wasn't old enough to run the country, this was

ruled by a "Regency Council", which was at first led by the

king's uncle, Edward Seymore, 1st Duke of Somerset, but from 1549 it was led by

John Dudley, 1st Earl of Warwick who two years later was appointed first Duke

of Northumberland. In the beginning of Edwards "reign" , the country was plagued by

riots and an expensive war with Scotland, which ended with defeat, and the British had to

give up not just Scotland, but also possessions in northern France to gain peace.

Under Edward, who was very interested in religious matters, Church of England

developed in a more Protestant direction than under his father.

The

Tudor Period was full of intrigues. A person could quickly rise in the ruler's

favor and even faster fall again, and the nobility was conspiring in order to achieve the best possible privileges. In 1549 Lord Somerset

was deposed as leader of the Regency Council due to "poor management of the

government", and he was replaced by John Dudley. Somerset took Edward to

Windsor Castle "to protect him" but in fact he was kept as hostage to

Somerset's ambitions. Somerset was arrested and committed to the Tower, but was

quickly released. Already in 1552, he was however arrested once more and executed after

an attempt to overthrow Dudley, who in the meantime had become Duke of

Northumberland. Dudley had his own ambitions - and his eldest son, Robert, was a

close friend of Henry's youngest daughter, Elizabeth, and perhaps her love

interest and probale lover,

but that's another story.

In 1553 Edward became ill with measles and shortly after he was stricken with

tuberculosis. It soon became clear that Edward was mortally ill, and Dudley took

the opportunity to further his own ambitions. When Edward died, his sister

Mary would be next in the line of succession, but because she was Catholic like

her mother, Dudley and many others with him believed that she would return England under papal control. Edward himself was also

a convinced Protestant, and at the same

time he believed, or he was convinced to believe, that his two sisters were not true born, and

thus could not inherit the throne. Like his father, he therefore wrote a document describing the succession , and

in this document his two half-sisters are not

even mentioned. Like his father had promised, he appointed as heirs, descendants of his aunt

Mary. On his deathbed, Edward was even more specific,

undoubtedly convinced by John Dudley, and appointed as heir to the throne his

first

cousin once remeoved, Lady Jane Grey, daughter of Frances Brandon and Henry Grey. John Dudley's interest in this

line of succession will become clear below.

Why Edward did not appoint his cousin, Jane's mother is unclear. Some sources

thinks that Henry VIII had directly left her out his succession act and that Edward respected this, while other sources

claims that she gave up the right of

succession in favor of her daughter. If this is correct, she probably fell under John

Dudley's powers of persuasion.

Lady Jane Grey

Lady Jane Grey was born in October 1537 (some sources believe that she was

born in

the spring of 1537 or in December 1536, but most maintain October 1537). She

was the first child of Henry Grey, 1st Duke of Suffolk and Lady Frances

Brandon, Henry VIII's niece. The name Jane was very rare back then, so it is

believed that she was named after Jane Seymore, who had given birth to Edward

VI few days after Jane herself was born. She had two younger sisters, Lady

Catherine Grey and Lady Mary Grey who were great-granddaughters of Henry VII. As a child she was given a first-class

humanist

education. She studied Latin, Greek and Hebrew with the

greatest capacity in those disciplines, John Aylmer, bishop of London and she studied

Italian with the Italian priest Michelangelo Florio. She was raised as a

Protestant (Florio was a former Franciscan friar who had converted to

Protestantism) and she exchanged letters with the Swiss reformer Heinrich

Bullinger.

Lady Jane Grey was born in October 1537 (some sources believe that she was

born in

the spring of 1537 or in December 1536, but most maintain October 1537). She

was the first child of Henry Grey, 1st Duke of Suffolk and Lady Frances

Brandon, Henry VIII's niece. The name Jane was very rare back then, so it is

believed that she was named after Jane Seymore, who had given birth to Edward

VI few days after Jane herself was born. She had two younger sisters, Lady

Catherine Grey and Lady Mary Grey who were great-granddaughters of Henry VII. As a child she was given a first-class

humanist

education. She studied Latin, Greek and Hebrew with the

greatest capacity in those disciplines, John Aylmer, bishop of London and she studied

Italian with the Italian priest Michelangelo Florio. She was raised as a

Protestant (Florio was a former Franciscan friar who had converted to

Protestantism) and she exchanged letters with the Swiss reformer Heinrich

Bullinger.

Jane did not enjoy her childhood and harsh upbringing. She found that no matter what she did, she could not do it well enough to satisfy

her over-ambitious parents, and she

complained to the visiting scholar and scientist, Roger Ascham, who was a

teacher of later Queen Elizabeth I, that "For when I am in the presence

either of father or mother, whether I speak, keep silence, sit, stand or go, eat,

drink, be merry or sad, be sewing, playing, dancing, or doing anything else, I

must do it as it were in such weight, measure and number, even so perfectly as

God made the world; or else I am so sharply taunted, so cruelly threatened, yea

presently sometimes with pinches, nips and bobs and other ways (which I will not

name for the honour I bear them) ... that I think myself in hell." In February 1547

when she was nine years old she was sent

away from home to be brought up elsewhere. It may sound brutal to modern ears, but it was

quite common for nobles at that time to have their children raised at least

partly by other

nobles. Jane was sent to Lord Admiral Thomas Seymore, brother of the late Queen Jane

Seymore. It is believed that Seymore himself planned to get married to one of

Henry VIII's two daughters but he failed in this. When the king died, he was still

unmarried, but shortly after Jane had moved in to his home, he married the

dowager queen, Catharine Parr and Jane spent the next year in their household. Jane

admired Catherine much, and when she died of complications after childbirth in

September 1548, Jane, then 11 years old, served as chief

mourner, a title which today sounds a bit ridiculous, but which was then a

very important honorable duty. She remained in the household until Thomas Seymore was

arrested in late 1548.This arrest was apparently prompted by Seymore's brother

Edward Seymore, the Duke of Somerset and Lord Protector of England. He

probably felt that Thomas' popularity with the king, threatened his own

position. Among the allegations he made was that Thomas Seymore allegedly tried to

arrange a marriage between his ward, Jane Grey and Edward VI. In 1549 Thomas Seymore

was charged with 33 cases of treason and was beheaded in the Tower, a fate

that almost three years later also happened Edward Seymore himself, as

mentioned above.

During these events Jane's father, the Duke of Suffolk

managed to avoid getting involved, and after Thomas Seymore's execution, he proposed a marriage between

Edward Seymores son, Lord Hertford and Jane, but this came to nothing. Jane

had moved back to her parents household after Seymores execution, but had

now become ward of

the new Lord Protector, John Dudley, a man whom she quickly discovered that she

could not stand. In 1553 she was still "available on the marriage market" ,

and she became engaged and under her protests but also under pressure from her parents married to Lord Guildford

Dudley, a younger son of John Dudley. This

may have had some influence on Dudley's interest in getting Jane Grey identified

as Edwards heir to the throne! Jane was 15 when she married Guildford Dudley.

Jane's Marriage

John Dudley had big ambitions. His

oldest son, Robert Dudley, may have had a romantic relationship with Henry

VIII's daughter, Elizabeth (later Elizabeth I ), but this never

developed into marriage. Dudley was a convinced Protestant , and therefore felt

that if either Mary, who was a Catholic, or Elizabeth, who probably loved his son,

but wouldn't marry him, should become queen, it would mean the end of his own

position and a definitive end to his ambitions of bringing the Dudley family on the throne of

England. But by letting his son, Guildford marry Jane Grey and persuade Edward

to make her his heir, Guildford would become king when Edward died. Jane was not

interested in being married to Guildford, but Dudley conspired with

her ambitious parents, and it was possibly because of this conspiracy that Jane's mother

Frances gave up her own claim to the throne. Jane was forced to marry a man she

did not know, and become daughter-in-law to a man whom she despised and hated

intensely. On May 25th 1553, she was married to Guildford while her younger sister, Catherine Grey

was married to William Herbert, 1st Earl of Pembroke. This mariage was annulled

before a year has passed, when lord Herbert tried to distance himself from the

Grey family. A third wedding that took place on that occasion was between Katherine

Dudley, a daughter of John Dudley and Lord Hastings, son of the Earl of Huntingdon.

John Dudley had big ambitions. His

oldest son, Robert Dudley, may have had a romantic relationship with Henry

VIII's daughter, Elizabeth (later Elizabeth I ), but this never

developed into marriage. Dudley was a convinced Protestant , and therefore felt

that if either Mary, who was a Catholic, or Elizabeth, who probably loved his son,

but wouldn't marry him, should become queen, it would mean the end of his own

position and a definitive end to his ambitions of bringing the Dudley family on the throne of

England. But by letting his son, Guildford marry Jane Grey and persuade Edward

to make her his heir, Guildford would become king when Edward died. Jane was not

interested in being married to Guildford, but Dudley conspired with

her ambitious parents, and it was possibly because of this conspiracy that Jane's mother

Frances gave up her own claim to the throne. Jane was forced to marry a man she

did not know, and become daughter-in-law to a man whom she despised and hated

intensely. On May 25th 1553, she was married to Guildford while her younger sister, Catherine Grey

was married to William Herbert, 1st Earl of Pembroke. This mariage was annulled

before a year has passed, when lord Herbert tried to distance himself from the

Grey family. A third wedding that took place on that occasion was between Katherine

Dudley, a daughter of John Dudley and Lord Hastings, son of the Earl of Huntingdon.

When Edward died John Dudley persuaded the Regency Council to keep the

death secret

and instead send a letter to Mary, that her brother was seriously ill and that

he wanted to see her. Dudley's ulterior motive was to lure Mary to London, where she could be arrested and

incarcerated in the Tower. At first Mary was lured

and left her home, but along the way she discovered the truth and instead of

continuing,

she began to gather an army from among her faithful Catholic supporters. At the

same time she sent a letter to The Council, in which she demanded that they

recognized her as the rightful queen. When the letter arrived, Dudley had

already gotten

the next part of his plan underway. The Council had written to Jane

Grey and summoned her to a meeting of the Council, which was taking place in Syon

House in West London, who was then a royal palace, but today serves as home of the

present

Duke of Nothhumberland. Fate works in mysterious ways.

Jane arrived not knowing that Edward VI had died, and she was (according to her own diary) very confused when two noblemen knelt

before her, kissed her hand and

called her "their royal mistress." She was then led into the Council of State

and Dudley led her to the stand that was reserved for royalty, and where

she had to take place while the whole assembly, including her own parents,

paid tribute to her. Only then was she told that Edward was dead and that he had

appointed her as heir to the throne. This information caused her to burst into tears, and her first comment was "I have no right to the crown, and

it pleases me not to get it. Lady Mary is the rightful heir." Both Dudley and

her own parents admonished her of her duty and ordered her to do what was

expected of her. Religious as Jane was, she thought she had to obey her parents

, even if she did not agree with them, so she agreed, but noted that she was

not the right woman for the role of regent.

The next day she was dressed in clothes in the green and white colors

of the Tudors,

while her husband was dressed in white and gold. They were then transported by

boat to

the Tower, where monarchs traditionally stayed between taking the throne and the coronation. Here an

appartement was prepared for her and Guildford and the

crown jewels were taken out of the treasury. This would be Jane Grey's last

journey, and she literally never left the Tower again. Along the way

towards Tower people along the river were completely silent in stead of rejoicing as the

should have been. It had just been announced publicly that the beloved Edward had

died

and that the throne was be taken over by an unknown, unwanted cousin. When they

arrived at the Towerthey were recieved by the deputy commander, Sir John

Brydges and the commander, the Marquis of Winchester. They handed over the keys

to the castle

to Jane, but these were instead grabbed by John Dudley, to make it quite clear

who had the real power. Jane and Guildford were now brought into the White

Tower, where the apartment was ready.

The nine day queen

Jane was taken to the audience chamber where she took a seat on the throne,

and was left with a few servants, among them her old nanny. Shortly after

Winchester arrived with some of the crown jewels and the imperial crown. Jane refused to

put on the crown and claimed "This crown has never been required, either by me or by

others in my name" , but Winchester explained that he just wanted to check if

it suited her. Eventually she gave in, and Winchester put the crown on her head.

Thus was Jane Grey unwillingly crowned as Queen of England on July 10th 1553, 15 years old. Later that day Guildford

asked her to make him king, which she

refused. He claimed , however, that he would make sure that both she and the

Parliament would make him king, but Jane was stubborn. As Guildford left the

room to " squeal to his mother " Jane sent for the Earls of Arundel and Pembroke and

explained to them that "if the crown really is mine, I will make my husband

a duke , but I will never voluntarily make him king. " Later she was

scolded by

Guildford's mother for nearly an hour, but she insisted that she would not make

her husband king.

Jane was taken to the audience chamber where she took a seat on the throne,

and was left with a few servants, among them her old nanny. Shortly after

Winchester arrived with some of the crown jewels and the imperial crown. Jane refused to

put on the crown and claimed "This crown has never been required, either by me or by

others in my name" , but Winchester explained that he just wanted to check if

it suited her. Eventually she gave in, and Winchester put the crown on her head.

Thus was Jane Grey unwillingly crowned as Queen of England on July 10th 1553, 15 years old. Later that day Guildford

asked her to make him king, which she

refused. He claimed , however, that he would make sure that both she and the

Parliament would make him king, but Jane was stubborn. As Guildford left the

room to " squeal to his mother " Jane sent for the Earls of Arundel and Pembroke and

explained to them that "if the crown really is mine, I will make my husband

a duke , but I will never voluntarily make him king. " Later she was

scolded by

Guildford's mother for nearly an hour, but she insisted that she would not make

her husband king.

Meanwhile, the Council had responded negatively to Mary's request and in doing

so stated that they regarded her as "illegitimate" and therefore she

had no claim to

the throne. The same message was published to the people of London, but they did not

care, as they were still grieving over Edward. At the church service at St Paul's

Cathedral on Sunday July 11th The Church of England declared it's support for Jane and stated

that both Mary and Elizabeth were "bastards" who did not have inheritance

rights. That evening a letter arrived from Mary dated two days previously,

in which she declared herself as queen and she asked that they tried to avoid

bloodshed. Jane was silent while the letter was read, but her mother and

mother in law broke down in tears. The Council decided to send John Dudley's two

sons, Robert Dudley and the Earl of Warwick out to meet Mary. Mary

had now gathered an army and was heading towards London and the two brothers arrived the

day after, while Mary's attention was elsewhere and did not have time to meet

with

them, which probably saved their lives.

For the next two days, we know little about what Jane was doing as queen.

We know that

she felt ill and she even thought that she was being poisoned by her mother in law,

because she still would not make Guildford king. There is, however, no evidence that

she was poisoned and she may have been sick with stress, or infected by bacteria from the uncovered

moat around the castle. On the 13th it became clear that Jane (or rather John Dudley) had serious problems. The people supported Mary, not Jane. The Council decided

to send an army under the leadership of Jane's father against Mary, but Jane

would not allow it, and instead John Dudley took command of the army, which

consisted of only 600 men. Meanwhile, Mary gathered more and more men around her,

and now the common people revolted and demanded that Mary was to be crowned as

queen. On the eighth day after the coronation, no one knew what

to do. The Duchess of Northumberland and Jane's father, the Duke of Suffolk came to

blows, again because of Jane's reluctance to make Guildford king, while Jane

could not stop crying. At the same time news arrived that the country's farmers

would not fight against Mary, so Dudley could not increase his small army.

The next day it was clear that there was nothing left to do. In Dudley's absence

the privy council (close advisors to the monarch), except for two members,

changed side and supported Mary in stead of Jane, presumably in an

attempt to save their own hides. The two remaining supporters were Jane's own father

and Thomas Cranmer,

Archbishop of Canterbury, but already in the afternoon Cranmer also switched

side.

That evening at around 6 pm Mary was officially proclaimed as queen, and Jane's

nine day reign was over. Jane's father visited her and explained the situation

to which she replied, "Can I go home now?" But she could not. She had to stay

in the apartment with her maids of honor to late at night, when she was moved

to new premises above the deputy commanders housing. Later she moved to a house on

Tower Green, a green area inside the castle. Her husband was imprisoned in

Beauchamp Tower also within the castle.

An even sadder end

Although she was a prisoner, she was not locked in a cell. She was allowed to

walk in the queen's garden and elsewhere within the Tower. She had three women to

take care of her, in addition to two ladies in waiting and a young man. She got a

respectable amount of money for her subsistence and

her conditions were on the whole rather good. On July 20th she was visited by the Marquis of

Winchester, who told her that some of the crown jewels were missing, and

demanded that she returned them. Jane claimed that she had relinquished

all she had been given, but Winchester demanded that she replaced the missing,

so she gave him everything she had of value. On July 27th, her father, the Duke of

Suffolk, was arrested for treason, and while her mother sent a direct appeal to

Queen Mary to release the husband, there is no evidence that she ever did the

same for Jane.

On August 22nd 1553, John Dudley was executed and in September of that year, the

Parliament stated that Mary was the rightful queen and simultaneously Jane Grey was

declared as usurper. Jane and Guildford were both charged with high treason and

so were two of Guildford's brothers and the Archbishop of Canterbury, Thomas Cranmer. Their cases were settled by a special committee chaired by Thomas

White, Lord Mayor of London and with several noblemen as members, among

others, the Duke of Norfolk and the Earls of Derby and Bath respectively. All

the accused were found guilty and sentenced to death. Among the evidence

against Jane were some documents that she had signed "Jane, The Queen" . She

was sentenced to be burned alive or beheaded what the queen liked best!

However, the imperial ambassador from the Holy Roman Empire could shortly after

send a report to Emperor Charles V that her life would be spared.

However, it wasn't for long. In January 1554 protestants rebelled against Mary. This

rebellion was led by Thomas Wyatt and Jane had nothing to do with it. The rebellion arose out of Mary 's decision to marry King Philip II of Spain,

just what Henry VIII had tried to avoid in his Succession Act. By marrying a

foreign king Mary was risking that England came under foreign rule. Unfortunately for Jane, her father, who had been released after his earlier arrest,

joined the rebellion, and that sealed Jane's fate. Mary decided that the executions of Jane and

Guildford would be conducted as originally planned, and they were set to take

place on February 9th 1554. Shortly after Queen Mary postponed the executions for three days,

to give

Jane time to convert to Catholicism. Mary sent her own chaplain to Jane ,

but she refused to convert, even to "save her soul" which was the

argument of the chaplain. However she became friends with the priest and allowed him to accompany

her to the scaffold.

However, it wasn't for long. In January 1554 protestants rebelled against Mary. This

rebellion was led by Thomas Wyatt and Jane had nothing to do with it. The rebellion arose out of Mary 's decision to marry King Philip II of Spain,

just what Henry VIII had tried to avoid in his Succession Act. By marrying a

foreign king Mary was risking that England came under foreign rule. Unfortunately for Jane, her father, who had been released after his earlier arrest,

joined the rebellion, and that sealed Jane's fate. Mary decided that the executions of Jane and

Guildford would be conducted as originally planned, and they were set to take

place on February 9th 1554. Shortly after Queen Mary postponed the executions for three days,

to give

Jane time to convert to Catholicism. Mary sent her own chaplain to Jane ,

but she refused to convert, even to "save her soul" which was the

argument of the chaplain. However she became friends with the priest and allowed him to accompany

her to the scaffold.

On the morning of February 12th 1554 Guildford was led out of his room and led to the public

execution place at Tower Hill. As he was not of royal blood he would be executed in

public and not private inside the castle. After decapitation his body was

taken back to the Tower on an open cart, where they passed right under Janes

windows. When she saw the body she exclaimed "Oh Guildford, Guildford" .

She was then fetched from her rooms herself and taken to the execution spot on Tower Green in

the same area where Anne Boleyn and Catherine Howard had been executed before her.

Mary had decided that she should be beheaded, not burned. According to one of

Jane's biographers, she made a short speech in which she stated that her sentence

was legal and that what she had done to Queen Mary was wrong. But she declared

herself innocent of having done anything with her own intent and "washed her hands in innocence

in the name of God and man." Then she recited Psalm 51 from the

Book of Psalms "Have mercy upon me, O God, according to thy loving kindness:

according unto the multitude of thy tender mercies blot out my transgressions.

Wash me throughly from mine iniquity, and cleanse me from my sin. For I

acknowledge my transgressions: and my sin is ever before me." The executioner asked her to forgive him, which she did and then she

said to him: "I beg you to do away with me quickly." She asked him to behead

her without her lying down, but that he could not do. She blindfolded herself and knelt but could not find the block with

her hands and

exclaimed in despair , "What shall I do? Where is it?" Thomas

Brydges, the deputy commander

helped her to find the block. While she was lying with her head on the block she quoted

Jesus on the cross and said, "Lord , into thy hands I commend my spirit." Then

the ax fell. Jane Grey never lived to see her 17th birthday.

Jane and Guildford were buried in the chapel of St. Peter ad Vincula within the

Tower on the north side of Tower Green and only a few feet from the place of

execution. 11 days later her father was also executed,

while her mother was set free. She married her Lord Chamberlain, Adrian Stokes in 1555 (not three weeks after her husband's execution,

as legend has it) and was pardoned by Mary. She was allowed to live at court with

her two

remaining daughters until hers death in 1559.

End of the Tudors

In later times Jane was regarded as

a martyr of the Protestant faith, a position that lasted for hundreds of years. Her name appears in several versions of Jonh

Foxe's Book of Martyrs . She has been the protagonist of several biographies,

novels, plays, paintings and especially movies.

Mary's reign was longer than Jane's but not long. She married Philip of Spain

who was her co-regent, and she tried to make England Catholic again. She and

Philip lived in different countries, but often visited each other. After such a

visit of Philip in 1557, Mary thought that she was pregnant (she had also

believed so in 1554 shortly after the wedding), but but no child was born. As

she had no children, she had to acknowledge her half-sister Elizabeth, as

the rightful heir to the throne after her. In May 1558, she became ill and

never really got over the disease that left her weak and without resistance. In the

fall of 1558 a flu epidemic broke out in London and on November 17th Mary died,

only 42 years old. Probably she also suffered from uterine cancer, which may have

further weakened her. Philip was at the time in Brussels and couldn't attend the

funeral, but he wrote in a letter to his

sister: "I feel some sadness to hear of her death." Here we

have a

husband "falling to pieces " over his wife's death - or something. Mary was

succeeded by Elizabeth, who chose not to marry, but probably had a

relationship with Robert Dudley, until he married. She reintroduced protestantism, and

the protestants, that Mary had persecuted cruelly, was returned to their former

posititions. Because of Mary's cruel persecution of their

co-religionists, they nicknamed her Bloody Mary.

Elizabeth died in 1603, leaving no heirs, and she became the last Tudor on the

English throne, which was taken over by James VI of Scotland under the name of

James I. However, there was a little Tudor blood in James, as his great-grandmother

was Henry VIII's oldest sister Margaret, but the Tudor Period ended with

Elizabeth.